Yesterday Spotify Wrapped dropped, and with it a new round of engagement bait as they included your “listening age”. Dunc getting a listening age of 55 prompted a full ten minutes of outrage in our team. I’m apparently 19.

Even as we complain that the Wrapped concept is washed, there’s still something we love about getting this glimpse into our own behaviour. We know it’s marketing, based entirely on storing data about us, but we still share and talk about the results.

This got me thinking about the kinds of online tracking we find fun and the kinds we find creepy. I’m nowhere near the privacy advocate I should be, because I understand all the horrors of surveillance capitalism, and yet I’m lazy and love convenience so when my AirNZ app detects I’m in the lounge and offers me my last coffee order to place again, I’m delighted. I know that I’m in a position of privilege where I can care a little less about being tracked, even if I shouldn’t.

I think when it comes to tracking, there are maybe three layers. The first is the self-mythologising data that we find cute: Spotify Wrapped, Strava’s Year in Sport, Duolingo streaks, Goodreads challenges. They’re made to be shown off and probably also to get us to not pay attention to how much data a platform stores about us. They turn our behaviour into a little caricature. You’re a person who listens to melancholy indie pop, and who tried to learn Italian for three weeks and then ghosted the owl.

The second is the ambient compliance data we tolerate: Google Maps location history, browser history, screen-time reports. We know it’s there; we’re vaguely aware we could scroll back through our past selves like CCTV but we mostly don’t. It sits in the background, occasionally popping up with an unnerving touch-grass warning about how much time we’ve spent scrolling.

And the last layer is the extractive data we resent: ad profiles, data brokers, “personalisation” that mostly translates to “we’re following you around the web until you buy the shoes you already bought”. The sense that your phone is listening to your conversations.

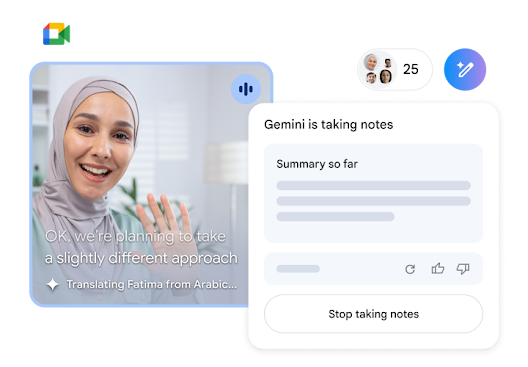

With the onslaught of AI, I feel more “recorded” than ever. Now you often turn up to a video meeting to find an agent in the call taking notes for someone.

We used to make a human-sized trail of our work in a notebook or a google doc. Now, there’s a tempting sense that we don’t really need to do that thinking anymore. We can just hit record and the machine will remember for us and so we can trade our own intentional memory for total recall.

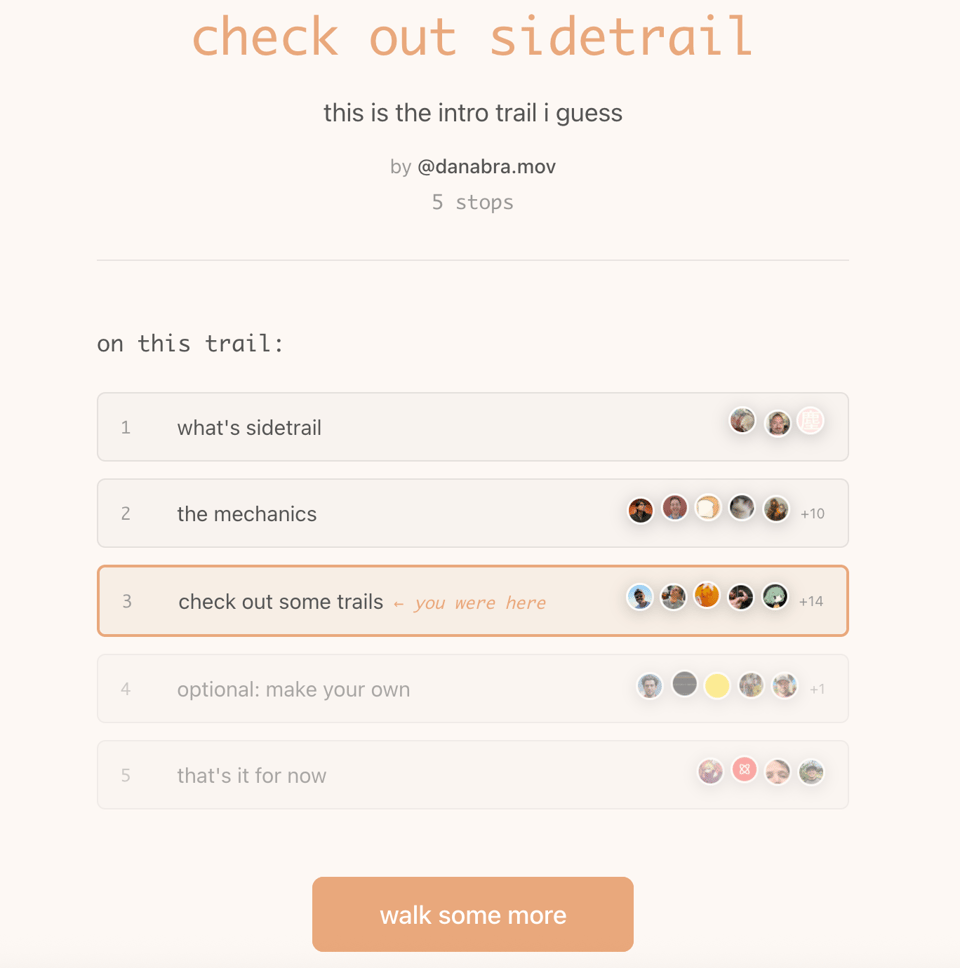

So now I guess I’m interested in the ways that I can use that to my advantage. We’ve talked a lot this year about the need to go exploring online again, and to save and share our journeys, so you can imagine how stoked I was to see Dan Abramov’s new project Sidetrail.

This is an ATproto app, so you can log in with bsky, but as a giant aside, I love the way Dan is campaigning to start using the language “log in with your internet handle” for the open web.

Anyway, Sidetrail is an app that lets you create and share a trail with any number of stops. You also get to see who else is walking the trail at the same time as you, which is a lovely design detail.

When I first saw it, it immediately clicked into place with something I’ve been circling around for a while: this idea of mapping our rabbit holes.

I talk alot about the perils of not controlling your scroll and letting the internet come at you like a firehose. And I keep advocating for what’s special about being online – especially in curious, nerdy spaces like fandom or research or creative work – which is more like a self-directed hike. You follow a recommendation, then a footnote, then a forum thread, then a friend’s link, and suddenly you’ve spent four hours learning about the history of bootleg concert recordings or mushroom foraging or competitive Excel.

Right now, that journey mostly disappears. Your browser history technically has some of it, but in a way that’s hostile to human comprehension. So it’s up to you to bookmark, and tag, and save, and draw meaning out of those links.

But here’s the extra bit I’m thinking about. If I’m already being tracked all over the bloody internet, what would it look like to have that trail be generated for me. For me to edit and choose what to share, but without that extra step of creation that most of us will never bother with. A tool like Sidetrail, but with the heavylifting done for me by the browsers and the platforms that are already stalking me.

I’m imagining something much more than just a list of links, of course. My most recent rabbithole started with me watching the new film Nuremberg, which as with almost all dramatisations of history just made me want more facts, and has led me over the last two weeks to youtube videos and podcasts and audiobooks and wikipedia articles and international law and the meaning of war crimes and how that relates to the current US drone strikes and whether Hegseth belongs in jail.

What I wouldn’t give to have the journey I’ve been on be presentable if I wanted to share it. I’d have to edit out some of the detours, obviously. The parts where I stopped to google potluck recipes for dinner on Saturday, or the long stream of Heated Rivalry gif sets, or the Love Island Australia discourse. But still, give me a publishable trail. Eventually, maybe, give me a way to make it beautiful and interesting — like this animation heavy idea Gaz shared with me. Let me drop in the side quests and the annotations and the “I changed my mind here” moments.

Because that’s the thing Spotify Wrapped reminds me of every year. The problem isn’t that the internet is keeping receipts; it’s that most of those receipts aren’t really for us. They’re for ad buyers and analytics teams and engagement dashboards.

If we’re going to be recorded anyway, I want more of the tools that flip the gaze around. Logs that start life as mine: private by default, editable, shareable on my terms. Trails instead of tracks. If the machines are going to remember everything, the least they can do is help us turn that mess into stories we can tell each other.

Let me take you with me when I go exploring. Let me go with you. And in between the doomscrolling and the engagement bait, maybe we can start to build a web where the history that matters most is the kind we choose to keep and share.

more good stuff

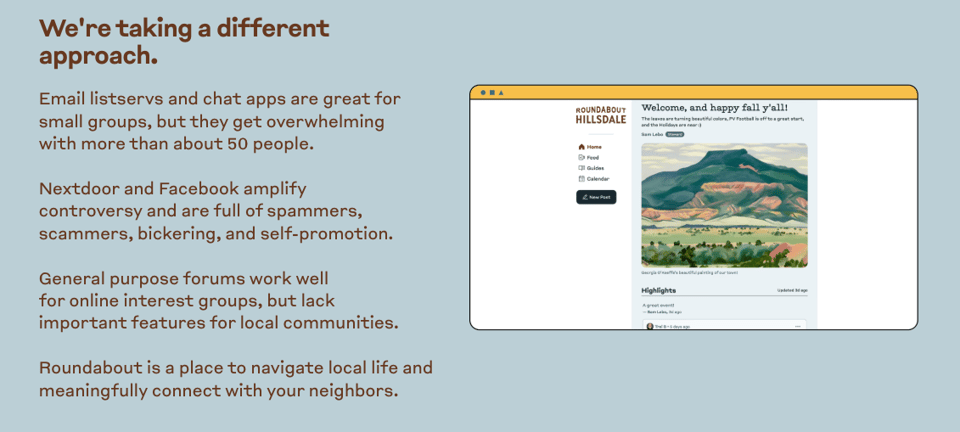

as you know I’m always thinking about the tools groups need to form online, so I loved the initial thinking from the team building (US-only at this stage) Roundabout.

back at the start of the year we talked about Mandalorian cosplay, and how the lore made it possible for people to personalise their armour, so I loved this article about the current Doctor Who and how the absence of one iconic costume democratises cosplay.

prompted by my mother asking me on the weekend if there was a place to comment on this newsletter (there is, on the web, but noone uses it), this piece about the history of the comment section. To be clear I love it when you reply and tell me things, but it is different than the old comments sections of yore.

finally, in my lego city

Forward this email to someone who says “where has the year gone?!”

You just read issue #49 of what you love matters. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.

-

I definitely don't want to track my rabbit hole/internet trails and then share them but the concept is interesting. I like connecting with people online, but I'm also backtracking a lot more into personal internet privacy-- like, do I really want to use the same username across all services? 10-15 years ago I did, and now I'm like...maybe not. Maybe also I don't want to link to them all from a Carrd, either, so other people can find me everywhere. Maybe I wanna have separate internet spaces for single identities, idk.

Anyway, hello comment section!

Add a comment: