I’m really excited to be heading back to Berlin to speak at Beyond Tellerrand in November. This is a gorgeous, carefully-curated single-track conference about the best of the web. If you’re in that part of the world, please come along.

culture gaps

This week I went to a public panel discussion on quantum physics — mostly to cheer on my bestie Andrew and newsletter reader Richard (hi Richard!), but also because quantum computing is one of those delicious topics that I know only the barest amount about and even that small amount makes my head hurt. Andrew and I flatted together when he was doing his phd, and he would gamely try and explain it to me using beer bottles and cigarette lighters, and I don’t really have any better grasp of it now than I did then.

Sitting at the back of a university lecture hall on a Tuesday night, I kept thinking about the gap that keeps these big ideas from most of us — gaps between academia and those of us who need an explanation simple enough to be illustrated with beer bottles, between what came to be known as “high” and “low” culture.

Last year Hylton and I went to the Royal Opera House to see Brian Cox’s Horizons show accompanied by the Britten Sinfonia. It was three of my favourite things — mind-melting space facts, insane giant full-screen photos from the JWST (Just Wonderful Space Telescope), and a live orchestra.

But they’re all things that often don’t feel that accessible, even for the curious. And in a moment when the broligarchs are telling us we should just ask an LLM to summarise big ideas for us — that we don’t need to set aside time to find things out for ourselves — I keep mulling on how we can bridge these gaps on- and offline.

Museums have been working for years to bring history and science to life for wider and wider audiences. Last year, the V&A Museum had a Taylor Swift songbook trail situating her costumes throughout the building — encouraging fans to walk through hall after hall of priceless and important history they might never have otherwise visited, in pursuit of something they love.

These exhibits are increasingly common. The Louvre creating a guided tour based on the works of art in Beyoncé and Jay-Z’s Apeshit music video. Or the Uniqlo x MoMA collaboration. Institutions of “high” culture making intentional efforts to become more accessible, often by meeting audiences where they are or integrating pop culture into traditionally “elite” spaces. Same thing with Shakespeare in the Park. Or the BBC Proms.

Or my darling Rob’s fabulous (BAFTA-winning!) show Rob and Rylan’s Grand Tour. From one review:

A third strand is Clark discovering high culture with the help of his more learned friend. “I wouldn’t say art intimidates me. However, people talking about art can intimidate me,” he admits. “I come from quite a working-class background and art wasn’t the thing that we had hanging up in our houses – it would be fake chandeliers from down the market.” Rinder is a taxi driver’s son who was raised by a single mother, but somewhere along the way he discovered classical music and Renaissance painters, and is now delighted to introduce both subjects to Clark.

One of the things I’m excited to do next month is visit The V&A East Storehouse, where you can consult the museum’s catalogue, pick up to five items using the Order an Object service, and then in two week’s time you get to visit these items yourself with a curator.

By opening itself up so completely, V&A East Storehouse offers critique as well as celebration…This is what the museum of the future looks like – an old idea that’s now been turned inside out, upside down, disgorging its secrets, good and bad, in an avalanche of beautiful questions, created with curiosity, generous imagination and love.

Now, back to the qubits. We live in an age of unprecedented scientific discovery. Quantum computers, if they pan out as predicted, unlock something exponentially more powerful than robotaxis. mRNA vaccines offer a great leap forward, allowing for vaccines to be designed faster and produced more reliably and cheaply. Our telescopes are seeing light from the beginning of time.

And yet, for many people, these breakthroughs feel remote — abstract — like they belong to someone else. Just as opera feels inaccessible unless you speak Italian and can afford a ticket, big ideas today often come wrapped in technical language and institutional distance. If only a handful of people understand CRISPR or AI ethics, then only a handful of people get to shape those futures. But if you bring these ideas into the cultural bloodstream — through art, humor, fandom, fashion — then you make participation possible. You turn passive audiences into active thinkers.

I’ve been writing a lot this year about how AI is destroying search, and I think people are only just starting to get to grips with that. Jay Rosen shared this from Julia Alexander at Puck this morning:

This is exactly what I mean: Google Zero — the post-search era. Google itself becomes a walled garden, full of lazy scrapes of badly-generated content, telling you to eat glue and rocks.

When I was a kid, I used to love coming across a Reader’s Digest (in a friend’s family bathroom, or a doctor’s waiting room).

But it was always a starting point for me — it sent me straight to the school library. I wanted to find out more about the hoax, or the failed invention, or the “miracle in the blizzard”. It was never the whole story.

I don’t want the kind of digest the broligarchs are selling: where chatgpt badly summarises a huge, revolutionary, world-changing idea and reads it in a boring AI-generated voice while I’m on my peloton so that I can get back to the grindhustle for the rest of the day.

So, as we think about the new web aesthetic, making our time online full of discovery, rabbitholes, shared process, exploration and yes, Big Ideas — as we try to become active surfers instead of passive platform-sitters again — I also want to think about how we bridge these gaps. How we give people a path out of the walls, and the confidence to take it, and the ability to further share with us all what they find.

more good stuff

Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower was published in 1993 and starts in 2024—a 31-year leap. Are creators imagining futures that are closer or further away? This is a new dataset of 2.5k narrative works set in the future, each tagged with its release year and setting, for you to play around with.

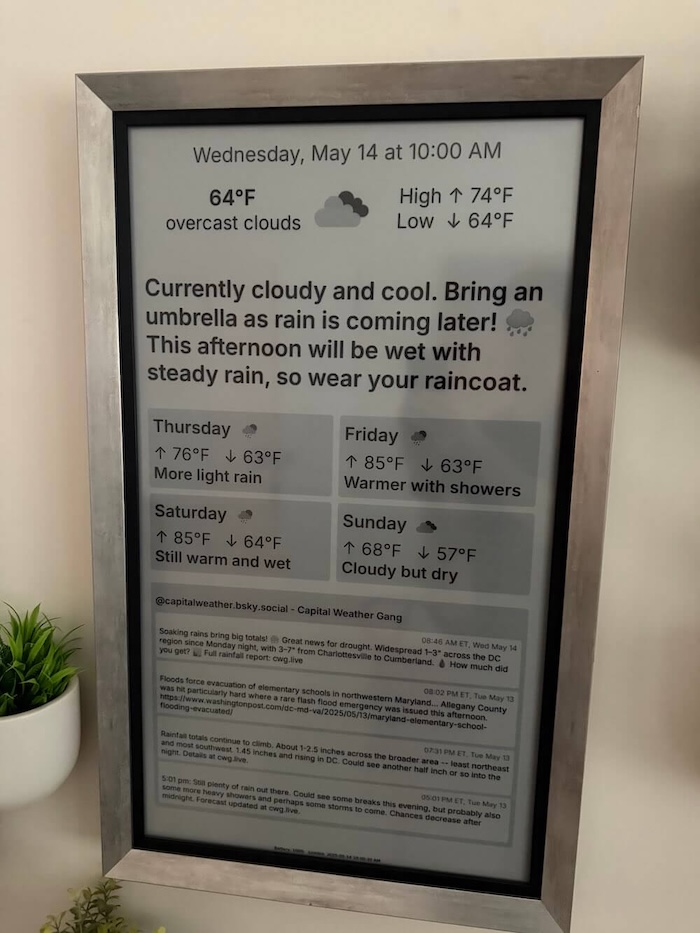

a good use of a (local) LLM: kid-friendly weather reports on an e-ink display.

via Today in Tabs CoolioArt, a YouTuber and special effects expert, decided the raptors in Jurassic Park weren’t terrifying enough, and inserted what we now believe are the most accurate representations of velociraptors into a few key scenes in the original movie.

finally, in my lego city

Forward this email to someone who doesn’t know what a qubit is.

You just read issue #27 of what you love matters. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.

Add a comment: