At the height of the Twilight fandom in the heady days of 2010, a new phenomenon started in the fanfic communities I was a part of, known as “pull to publish”. Up until that point, the boundaries between fanfic and traditionally published novels had been pretty sacrosanct — tied into a broader taboo around the legal status of fanfic and the foundational non-commercial ethos that kept everyone “safe” (i.e. if you weren’t making money off your lil stories, there was no grounds for IP holders to establish financial loss). But the 2010s made publishing books much cheaper, and a number of small vanity presses sprung up (often run by fans), offering to turn popular fan stories into “real” novels.

Twilight seemed ripe for this phenomenon because the stories fans were writing were overwhelmingly not about vampires. The most popular novel-length fics of the day recast Edward and Bella in mafia, sporting, or coffee shop romances. They were mountain climbers, or journalists, or tattoo artists. And so to file the serial numbers off and give the characters different names was a relatively straight-forward edit, and suddenly you had a conventional romance novel with a baked-in audience.

“Pulling to publish” referred to taking your fanfic down off fanficdotnet or AO3 and telling your readers they’d soon be able to buy a commercial copy of it. The most famous story pulled to publish was, of course, the juggernaut Fifty Shades of Grey. But while that project was ultimately the most successful, it was only one of several stories that made the leap at the time. Beautiful Bastard (based on Twilight fanfic The Office) became a NYT bestselling series published by Simon & Schuster. Gabriel’s Inferno (orginally a fanfic called The University of Edward Masen) was a two book series eventually adapted into a film.

While the publishing industry kept looking for its next Cassandra Clare (originally a Harry Potter fanfic crossover) or EL James, there were few follow-up hits. With the exception perhaps of the After series of novels based on a popular One Direction story, which have now turned into a critically-panned but financially successful series of movies.

The discomfort in fandom around these efforts is usually born out of a sense of being “used” in some way. EL James in particular made no secret of the fact that she’d considered her time in fandom an experiment in building up an audience she intended to capitalise on. You can find a good discussion on the dynamics at play in this tumblr post.

The lack of a ready stream of crossover hits is also — I think — because there’s something really different about a fanfic (even a novel-length one) and an actual novel.

Fast forward a decade, and a few things have changed substantially. Self-publishing, particularly through Kindle Unlimited in the romance genre, has become a genuine way for prolific authors to find a paying audience for their work directly and without traditional publishing deals. At the same time, the influence of booktok has propelled romance into the mainstream. Romance has always been the most commercially successful fiction genre, but has been hampered by the classic “it’s nonsense for ladies” that has left it sidelined with the stereotyped Harlequin covers and Fabio. (Completely unrelated, but if you’ve not watched Bobby Fingers sculpt Fabio getting hit in the face by a goose, go do that now. Fabioooo!)

Now, when every bookstore has a booktok shelf or table front and centre, publishers are paying attention. And they’re looking for baked-in audiences - marketing directly to fans no longer hiding their interest in the trope-driven fiction that they’re hungry for.

By 2023, Vulture was writing about the fanfic to publishing pipeline going mainstream:

The appeal is understandable: Fic writers bring knowledge of how to market a story and build an audience, a boon for editorial houses. The fans authors have gained writing fic will buy books, in some cases carrying them to the best-seller list. For writers who demonstrate a facility for telling a certain kind of story, the process of transitioning into writing traditional books is as much a matter of format and structure as anything else.

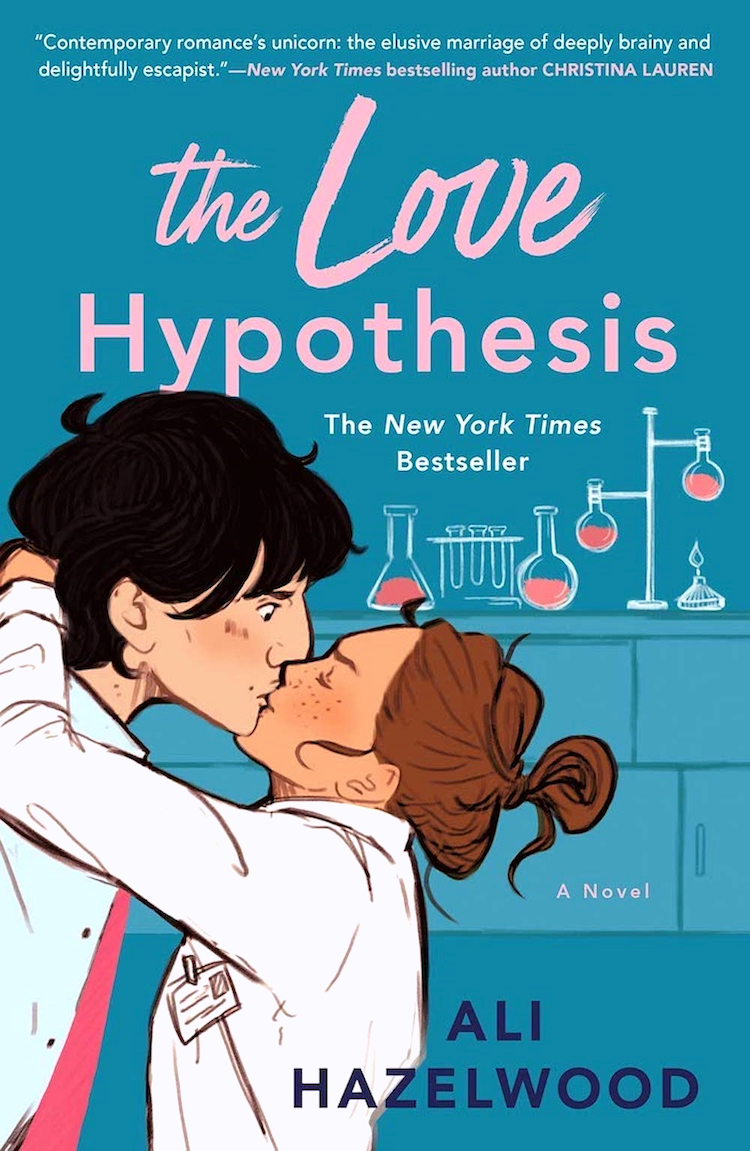

Ali Hazelwood’s The Love Hypothesis was based on a Rey/Kylo Ren Star Wars fic. The cover art didn’t make any attempt to hide that — a nod to the readers who’d loved the story in its original setting.

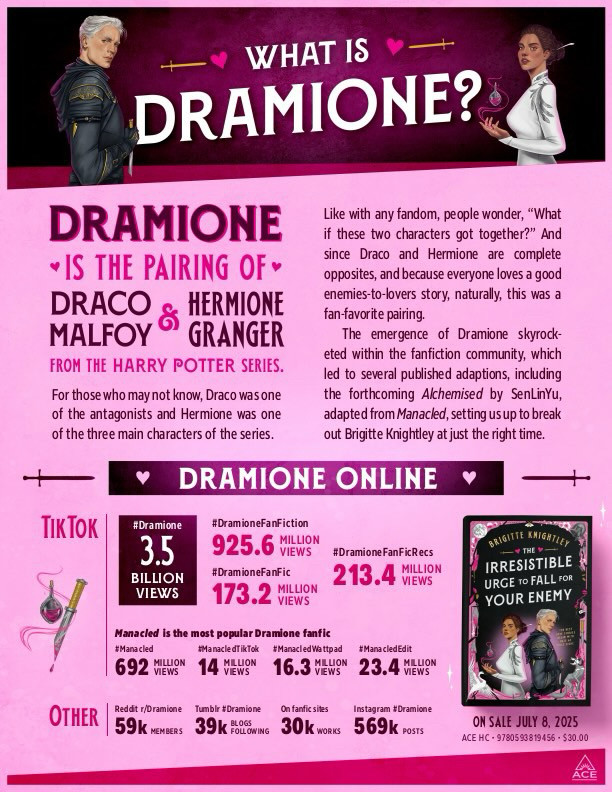

But now, we have a new sting in the tail. Tiktok is currently awash with new fans discovering Dramione — the Harry Potter fanfic pairing of Draco Malfoy and Hermione Grainger. And publishing houses, taking note, are bringing three of these stories out this summer.

More than just nodding to the books’ origins with some cute cover art, the promo campaigns for these books from the publishers are leaning right in:

All of this might have just felt like a bit of a cringe fourth wall break, but given these stories come from the Harry Potter universe, they’ve produced a much more volatile result.

JK Rowling’s continued, gloating transphobia, and her funding legal efforts in the UK to dismantle trans rights, has made it clear that anything that puts a single cent in her pocket is something you should avoid like the plague (looking at you, HBO). Here we have a much muddier swamp — with fanfic authors looking to profit off the same IP, and not being at all coy about it.

This has blown up in recent weeks as Romance Con (a convention celebrating romance authors and readers) first invited author Julie Soto to participate, and then uninvited her when the backlash became enormous, and finally parted ways with the conference’s management company (who also run HP conventions). Kayleigh Donaldson has written about this fully here.

But as a queer Scot who has watched Rowling decimate my country’s LGBTQ+ community through her well-funded hate campaigns, then had to walk through Edinburgh and see tourists giddily take selfies on Victoria Street in their Hogwarts robes, I have zero patience for this mealy-mouthed middle ground. Let Harry Potter die. Let it become irrelevant. Let it become such a financial drain that its presence on bookshelves lowers the value of surrounding titles. Only then will a hell of a lot of us feel safer. It shouldn’t be harder for you to let go of a children’s book series than it is to let queer and trans people know that you’re in their corner. At the very least, you shouldn’t be paying hard cash for fanfiction. Surely on that issue, we can agree.

Soto, for her part, seems to think that her fanfiction is reclaiming the material from JKR (archive) — an argument that many in fandom have made, but which holds a hell of lot less water when your publishers are directly marketing your book as Dramione fiction.

Knightley and Soto are aware of the backlash and have their own thoughts on navigating work associated with Harry Potter and Rowling. “It’s extremely disheartening,” Soto said, “and, frankly, makes me angry to have something that I love tarnished like this in not only my eyes but everyone’s eyes. But I think also a lot of times, fan fiction is an act of resistance against the created material.”

For Knightley, too, fan fiction is a way to take back ownership of a series she once loved “that has now been tainted by the author’s views and behaviors.”

But can a traditionally published story escape its fanfic origins? Jarrett isn’t so sure. “If we really were trying to reclaim something and take it away, we wouldn’t be still utilizing … that intellectual property to try and bring in readers and market it,” Jarrett said.

Garbage Day readers will have already had a good summary of all this drama this morning. The piece I want to add is really that this is another great example of marketers misunderstanding fandom dynamics.

It’s easy to see why publishers are so tempted: a ready-made audience, a cultural flashpoint, a rising author who already knows how to build community and write what readers want. But this whole mess is a case study in what happens when marketing teams latch onto fandom signals without understanding fandom values. To some, it might look like reclaiming a beloved narrative. But to many others — especially queer and trans fans who now associate the original work with real-world harm — it feels like betrayal dressed up as cynical promotion.

What’s being overlooked is that fandom isn’t just a reservoir of content to be mined or a demographic to be sold to. It’s a culture. One with norms, ethics, and long memories. When that culture is flattened into a sales funnel, you miss the nuance. You lose the trust and you court the kind of backlash that isn’t just about one book or one author — it’s about who gets to belong, and who gets left behind.

In the end, it’s not enough to ask, “will this sell?” The better question is: “who are you selling out?”

For the next month or so, this newsletter will be coming to you from London. Sing out if you’re there and want to catch up for coffee xx

more good stuff

-

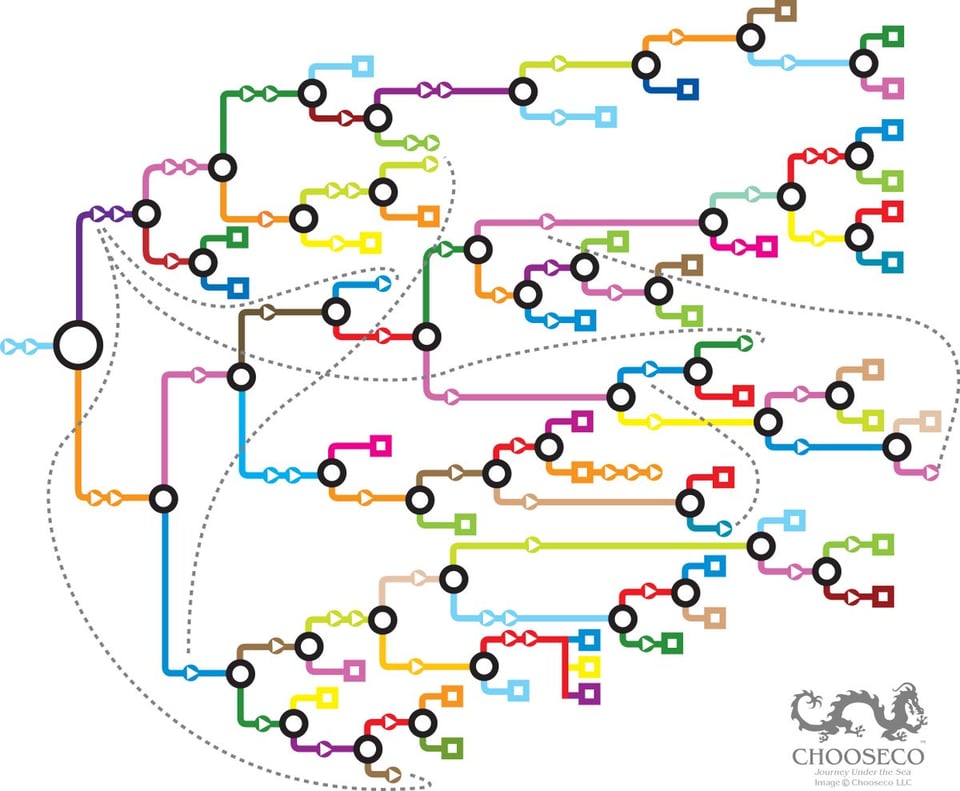

This isn’t new but I hadn’t seen it when I wrote about Choose your own Adventure books a few weeks back. Since 2004, reprints of the original books come with maps showing you the branching parts of the story (via kottke.org).

-

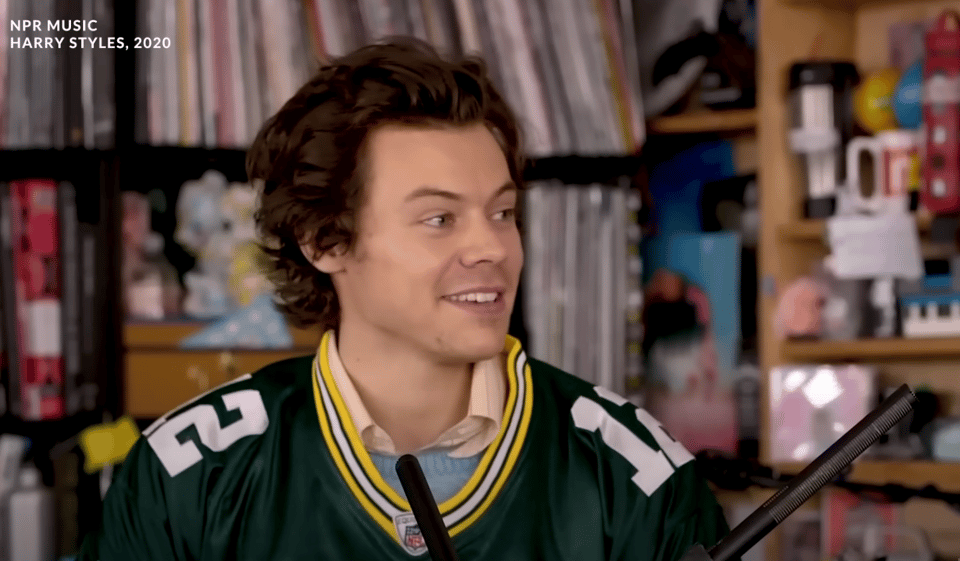

I absolutely love NPR’s Tiny Desk concerts, so this behind the scenes tour of the set was catnip for me even before I discovered Harry was in it.

hi baby

-

This thread popped up on Bluesky and had me rapt, so I was glad there was a full blog post about it.

eyes and ears

What I’m watching and listening to this week.

- As you all know, I’m never not thinking about cults. Youtube sends me a steady diet of “essays” where people cobble together unoriginal summaries of stuff everyone already knows (Tom Cruise, a scientologist? Imagine). But Let’s Talk About Sects is a great, original, well-researched pod about high control groups packed with interesting interviews. Start with this great ep about Falun Gong.

- The cancellation of The Late Show with Stephen Colbert is obviously a travesty. Worth watching: Jon Stewart’s response; all the late night hosts turning up in support.

- Untamed (Netflix, with national treasure Sam Neill) is a police procedural set in Yosemite and while it’s not doing anything incredibly groundbreaking I’ve decided I really like a procedural in an unusual setting (see also: Vigil (BBC) - set on a submarine) plus the landscape shots are gorgeous. CW: historical child loss.

finally, in my lego city

Forward this email to someone who likes cake.

You just read issue #30 of what you love matters. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.

Add a comment: