Look, I’ll confess, I’ve never been a General Admission girlie. I can understand the thrill of being as close as possible to your fave, but when I go to a concert I like to be able to go to the bar, or the bathroom, and come back to my spot. I say now that it’s because I’m old, but I’ve pretty much always been that way. I think the last time I really tried to get to the front of a concert was Michael Jackson’s History tour, which shows just how old I am. If I buy GA tickets for a smaller venue, I’m at the back dancing by the sound desk, wine safely in hand.

But I get it — for some fans, being “at barricade” (i.e. pressed as close to the stage as it’s possible to be) is the pinnacle of a live concert experience. And to secure that spot, you need to be first in line.

Over the years when I’ve talked about fans I’ve always made sure to point out that it’s not just teen girls who like to queue. Sneakerheads do it. Apple fanboys do it (or did it, before the queue moved online).

Queuing for fan experiences is also definitely not new. Circa 1920, hardcore opera-goers in Vienna would line up the night before famous singers’ performances and stay awake to make sure they got tickets as soon as the box office opened. In Aotearoa in 1937, all-night queues for football seats was considered a societal problem. In 1944 Sinatra’s fans waited in the street all night to buy tickets. Then Beatlemania hits and camping becomes a regular phenomenon, whether you want concert tickets, Star Wars tickets, or seats at Wimbledon.

For pop fans, camping out has become a real ritual for a certain subset. I loved this thesis about camping culture that dives into all of this in detail, including the meaning of these secondary interactions for fans and their value as “rites”:

Attending a concert is not morally the definition of the biggest fan, nor is attending front and center. However, it is understandable why fans may feel an anxious desperation to do so in order to understand their own identities, as well as to proclaim them to others. The validation of the perfect primary interaction ritual is not only a motivator to the queue, it is a way to prove to yourself, to others, and in some perspectives, to the artist that you are a good fan. That these experiences and the meanings we derive from them matter, because they do.

During the Eras Tour, fans in Argentina “camped” (multiple fans rotating through several tents) in line for over five months. This seems unhinged to outsiders, but the line is where you trade rumours and tips (“They’re opening a second merch truck at Gate 7”) and share snacks and phone chargers. It’s where you make friendship bracelets, literally, in the case of Swifties; Target’s recent midnight release party for Taylor Swift’s The Life of a Showgirl leaned into this by adding bracelet-making stations and a live DJ to its late-night queues. It’s community, and it’s extending the experience of the concert — making it last that much longer. Here’s a first-hand account:

Although camping isn’t for everyone, I have never felt more accepted and safer in a crowd of people. We all looked out for one another out there, by doing food runs and taking turns buying cases of water. Sleeping on the concrete was not the most ideal, but waking up to smiling faces as we moved closer to the venue was more than worth it. Meeting people who cared to listen to what I had to say about him as I spoke and did not just brush me off as some crazy girl because they too felt all that I felt for him. Making eye contact with Louis Tomlinson after following his overall journey throughout the music industry he’s made in the world for over the past ten years. Yes. It was all worth it.

Of course, none of this is neutral. To camp out, you need:

Time you can afford to “waste”

Relative physical safety on the street at night

A body that can cope with cold and discomfort and no sleep

A job, or parental situation, that won’t implode if you disappear for 36 hours

For any of this to exist, fans have to decide, informally and collectively, how things are going to work. In the last decade or so, that’s meant fans coming up with their own systems and rules. Numbers are written on your hand in sharpie (or now that you can buy them readily, numbered wristbands are handed out) to preserve your place in line. There will be rules about leaving the line, or letting people join you, or whatever. The first time I saw this in action, before a Harry Styles concert at MSG, these self-appointed fan leaders were carefully martialling the queue across the street in rush-hour Manhattan.

Cities and organisers have always been uneasy about these lines. After various all-night queues for concerts and sporting events, councils and venues periodically announce that they’re banning camping, or moving to ballot systems, or issuing official numbered wristbands to stop people lining up early. Some of that is genuinely about safety. Some of it is about optics. A line is a very visible sign of demand, but it’s also a very visible sign of inequality: who is allowed to occupy public space, whose excitement counts as charming and whose counts as loitering.

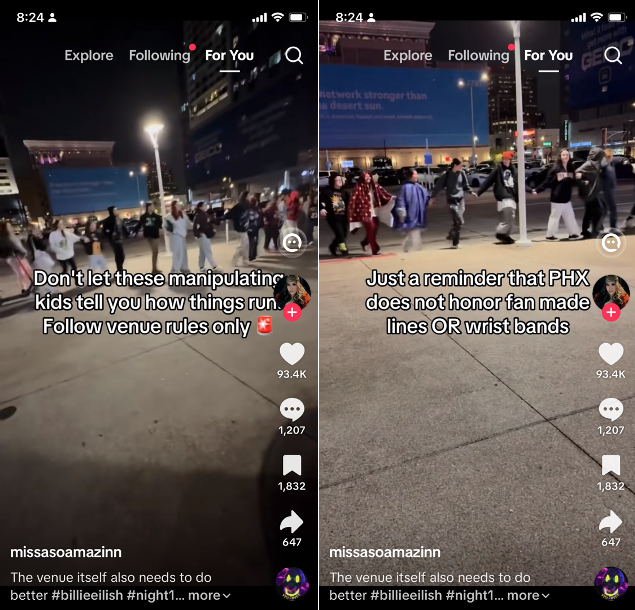

But in the last month or so I’ve noticed a real spate of tiktoks arguing about camping culture and it’s validity. On the one side are fans often encountering the practice for the first time, disbelieving that anyone would honour an unofficial system, and just heading to the doors.

On the other side are fans defending the practice of fan rules and systems on the basis that it increases safety, has been going on for years and years, and rewards fans who’ve put in the time.

On some level, this whole argument is really about who gets to decide what counts. Who gets to say “this is the right way to queue,” or “this is fair,” or even “this makes you a good fan.” The people on tiktok going, “I don’t care what number you’ve got written on your hand, I’m just walking to the doors” are bumping up against a whole invisible infrastructure that other fans have been building for years.

And that’s the bit I keep coming back to. I don’t think camping should be a moral barometer. You’re not a better fan because you slept on concrete, and you’re not a worse one because you turned up at doors-open and went straight to the bar (hi, it’s me). But I do think the existence of camping culture tells us something important: that if you leave a vacuum, fans will fill it. If venues and ticketing systems won’t design for fairness and safety, fans will try to do it themselves, with sharpies and spreadsheets and sheer force of will.

It’s not really about whether camping culture is good or bad. I think we should ask what would it look like to treat the impulse to camp as a design brief, instead of a nuisance. To build systems that assume people will want to show up early, to look after each other, to make the experience bigger and longer than the two hours on stage.

You don’t have to sleep on the pavement to be a real fan. But the next time you walk past a line of kids in blankets outside a stadium, it might also be worth remembering: this is what it looks like when something matters enough to them that people are willing to build a whole tiny, temporary world around it.

more good stuff

we keep bemoaning the destruction of google by AI slop but artist Tega Brain has done something about it, creating Slop Evader, a chrome and firefox extension that will only return content created before ChatGPT's first public release.

Since the public release of ChatGTPT and other large language models, the internet is being increasingly polluted by AI generated text, images and video. This browser extension uses the Google search API to only return content published before Nov 30th, 2022 so you can be sure that it was written or produced by the human hand.

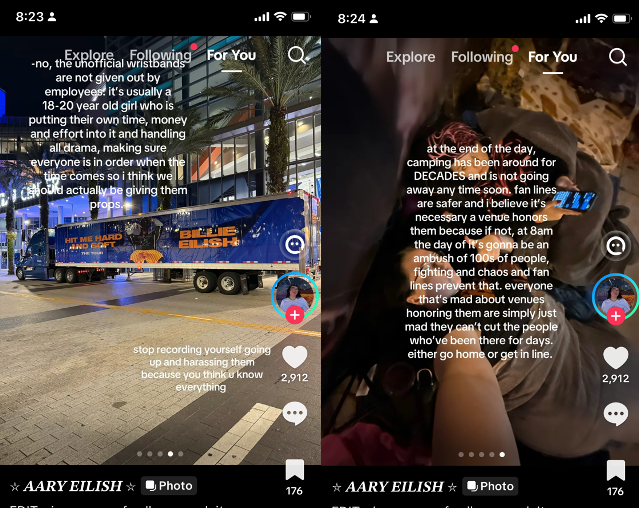

when I talk about the “good” internet I’m using it as a shorthand, and lots of other pundits(?) use other shorthand (e.g. the indieweb, the poetic web etc) and so I was interested in this (via Daylight) on the “post-naive internet”.

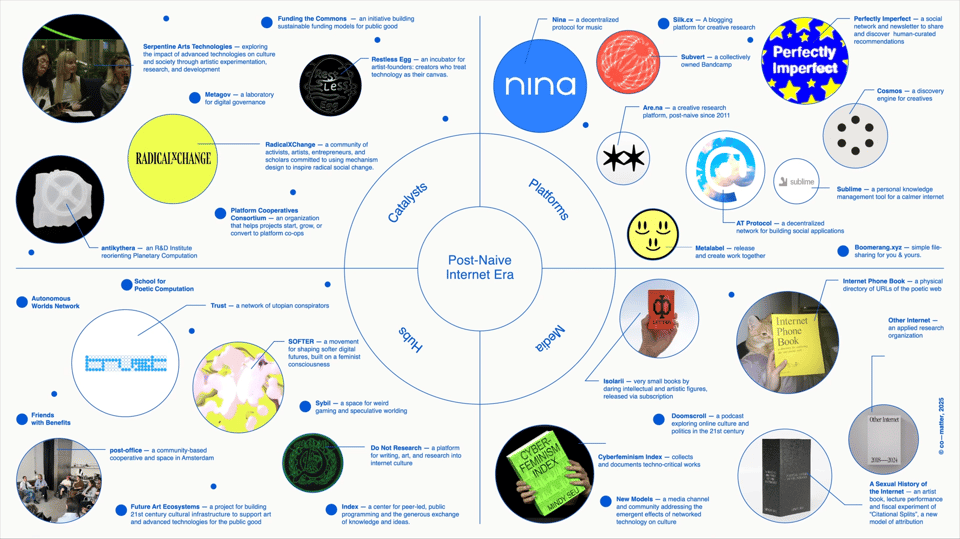

also as you know i love maps of course it was the fans of the hot firefighter show that prompted this (insert eyeroll), but I’m still chewing on lots of things that come out of this piece on fan favourite poet Siken.

transformative fandom vs the author part eleventy million

finally, in my lego city

Forward this email to someone who likes a mosh pit.

You just read issue #48 of what you love matters. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.

Add a comment: