This week tickets for Harry Styles’ upcoming Together Together tour went on sale and for the millionth time in the nine years of his solo career I found myself in the trenches of the ticket wars.

If you’re fortunate enough to not stan a stupidly popular musical artist, or, idk, don’t want to go the Superbowl or the Olympics, you might have managed to make it through life without considering Ticketmaster your actual nemesis. I am very old, so I still remember being able to queue up for tickets in the street that were sold in record stores (Big Day Out) or calling to buy them on an actual phone (Michael Jackson). Now, the whole thing is a landmine of competing presales, insane prices, false scarcity, scalpers and bots.

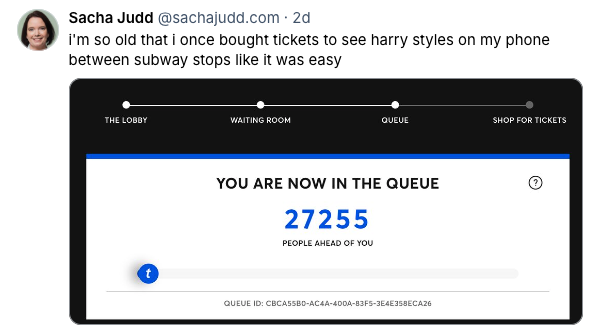

This happens every time a major artist tours now, but it feels particularly acute with Harry. His shows sit right at the intersection of pop monoculture and a deeply emotional fandom. People don’t just want to go — they feel like they need to. Missing out doesn’t feel like skipping a night out; it feels like being locked out of a cultural moment you’ve already invested years of your life in. A waiting room feels less like a queue and more like a gamified panic attack.

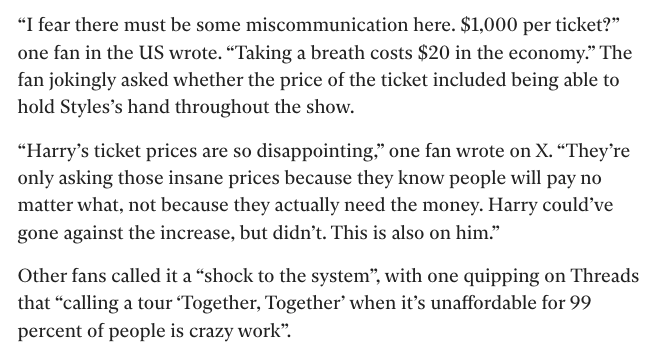

Let’s be clear. It costs too much to go to a concert. Live music has always been a stretch. But in the last few years, ticket prices have detached from almost any shared sense of what a concert “should” cost.

Arena and stadium tickets regularly land in the $250–$500 range before fees. “Best available” increasingly means algorithmic pricing, not better seats. That means surge pricing, like an uber. As you become increasingly desperate zooming around a stupid map looking for seats they are going up in price before your very eyes.

By the time you add service charges, travel, merch, and accommodation, a single night out can quietly turn into a four-figure decision. And look, I have no kids and disposable income. I can do these sorts of unhinged things with my money. But most people can’t.

This isn’t just inflation. It’s a shift in what live music is for — and who it’s for. A system that once relied on scale (lots of people paying a reasonable amount) now relies on intensity (fewer people paying as much as they possibly can). It’s a response to streaming, and how little artists can make from their music now. And it’s a response to the costs of touring, which have soared post pandemic.

There’s a sense that as a fan whatever you do, you’re being ripped off. Pay a bit more than you want in the rapidly-selling-out presale, and you’ll suddenly find the artist adds more dates, releases more tickets, or the demand in the general onsale isn’t really there and prices come down. During the Eras Tour, I had several friends reach out for advice on how to get tickets. My best advice is always to hold your nerve and wait. I’ve never failed to get a good ticket to a show I’ve wanted to see about three weeks out when the hospitality holds are released and fans put tickets they can’t afford or don’t want up for resale. But I was still up at 5am this week trying for Harry’s NYC presale, so I don’t even take my own advice. He is performing THIRTY nights back-to-back at Madison Square Garden. The presale closed before Luce and I even made it within 10k people of the front of the queue.

And the worst part is I’m not just competing against other fans. I’m competing against scalpers who coordinate their actions in Discords, sweeping up tickets and dropping them on reselling sites within minutes. And while Ticketmaster talks a good game about what they’re doing to defeat the bots, the reality is it looks good when a concert sells out in minutes — so how hard are they really trying?

Presales are framed as rewards for fan loyalty, but in practice they fragment ticket inventory making it impossible to tell how many seats will be available and at what pricing tiers, and they artificially inflate the sense of urgency. They weaponise demand from the people who are the artist’s biggest supporters.

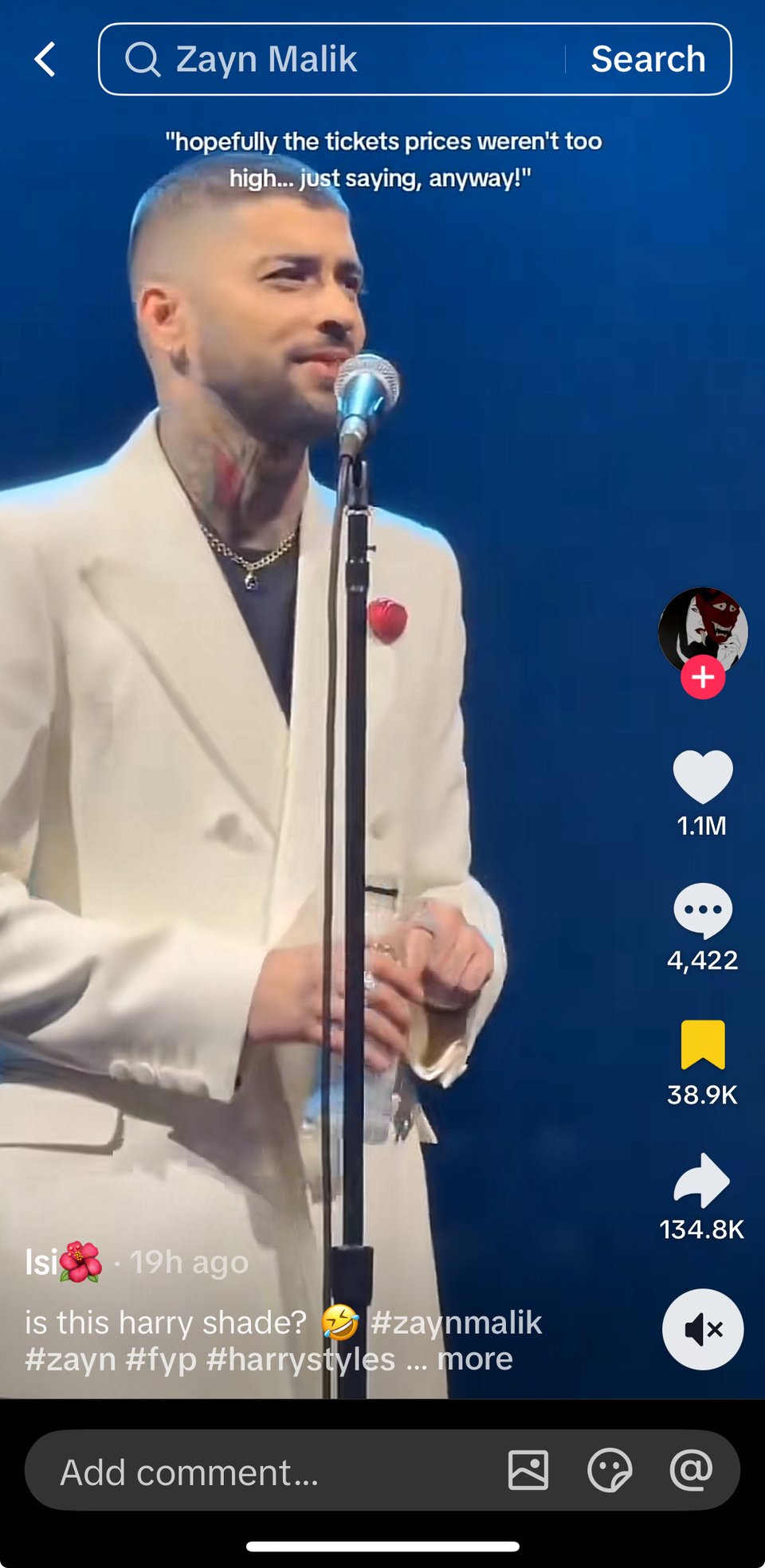

And it sucks for artists too. The people who can afford the VIP packages are often not dedicated fans, but suits being wooed, corporates, industry. The last people that you want up the front. Halsey has called this out. Chappell Roan said it was “weird that VIP think they’re too cool” to do her Hot To Go dance. Charlie XCX called out an LA crowd where the pit wasn’t singing.

Everyone agrees the situation is terrible. We know that artists can’t opt out of this system, Ticketmaster is a monopoly and as Pearl Jam famously found out, thumbing your nose at the infra just loses you venues. What can we do to change it?

Some artists have been active in their attempts to make things better for fans. Olivia Dean recently spoke out about the exploitative prices being charged on Ticketmaster resale, and the company did agree to cap resale amounts and provide some fans with refunds.

Ed Sheeran used one authorised face-value resale platform, and gave fans who had purchased unauthorised inflated-value tickets a letter to help them obtain refunds.

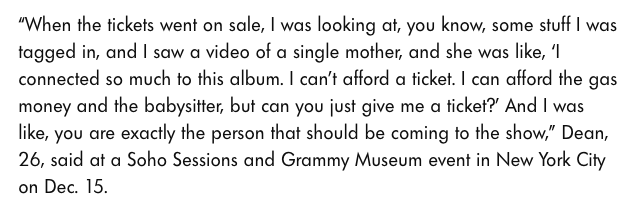

But we need to think bigger in terms of change. Monia Ali wrote a great proposal for a fan-first ticketing industry that’s worth reading in full. She argues for cheaper presale, local allocations, rush tickets/lotteries, waitlists and more. All things that work well in other spaces like theatre, and would increase accessibility, reward fan loyalty, and still allow for high priced packages for people who want them.

The long-term risk here isn’t that fans will stop wanting to go to concerts. Passion is remarkably resilient. The risk is that fans start to feel like the relationship is extractive rather than reciprocal.

When every tour feels like a financial stress test, fandom becomes something you survive rather than enjoy. Harry going on sale this week will break records. Tickets will vanish in minutes. Screenshots of eye-watering prices will circulate. None of this will be surprising.

What would be surprising — and genuinely game-changing — is a system that treated fan passion not as something to be squeezed to its breaking point, but as something worth protecting. Because once trust goes, no amount of dynamic pricing can buy it back.

more good stuff

while writing and speaking about conspiracy thinking I spend a lot of time thinking about the spread of misinformation. This study on “prebunking” (showing social media users a short innoculation video) is super interesting.

Instagram users in the treatment group were significantly and substantially better than the control group in correctly identifying emotional manipulation in a news headline. Moreover, the inoculation effect remained detectable five months later.

days later I am still thinking about this amazing long read about how a cold case of infanticide was cracked revealing a fraudulent branch of toxicology with such wide-ranging impact.

“I am not aware of any cases in the U.K., or elsewhere in the world, where breast-feeding by women who were on either morphine or codeine—which has been in use for more than a hundred years—has caused death,” Bateman said. “I am familiar with patients whose babies have died after a caregiver gave the opiate directly.” Juurlink listened in silence. The candles flickered. Bateman took a sip of wine, then leaned across the table and said, “David, whatever the intention, that baby was poisoned.”

last year we talked about the right-wing playbook being run whenever you see a famous woman being smeared all over social media. Kat Tenbarge has written a great piece on how that’s grinding to life yet again in the drama surrounding the Beckhams.

finally, in my lego city

Forward this email to someone you want to go to a concert with.

You just read issue #58 of what you love matters. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.

Add a comment: