A few weeks ago, we talked about what it’s like to be young and online at the moment, in light of the introduction of age-verification laws in the UK and some US states. But given the increasing sweep of these measures, and the sort of shrug most people give them, I want to go a bit deeper on it. If you feel like you know all this already, skip to the end where I hit the new things I’ve been thinking about on the topic this week.

When I talk about what’s wrong with the current attention economy, people often raise the suggestion of social media bans for young people as a possible solution. If the internet was a nightclub, we’ll all be queuing at the door soon, fumbling for our wallets, trying to prove our age before we can get in.

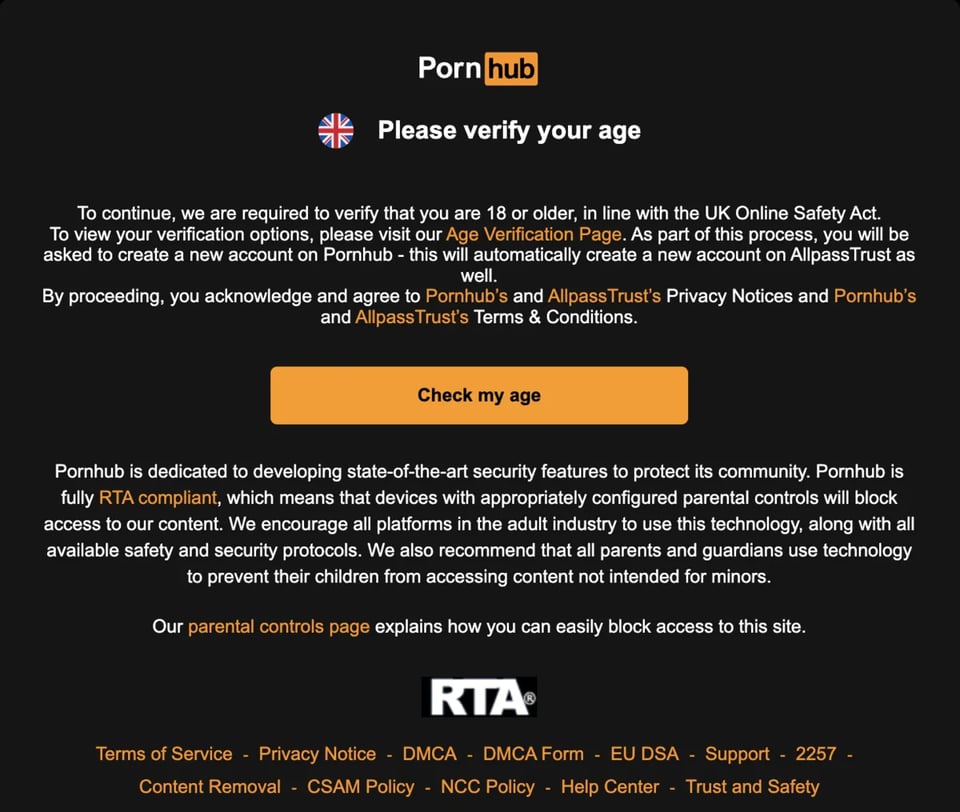

In the UK, the Online Safety Act came into force this July, giving Ofcom sweeping powers to require “robust age checks” for websites that host porn or other content considered “harmful to children.” Services that don’t comply face fines of up to 10% of global revenue. In practice, this means that sites from Reddit to Steam are rolling out new age-verification systems, often using third-party vendors, who ask users to upload an ID document or a selfie for facial recognition. Wired calls it “the age-checked internet”.

And the UK isn’t alone. The EU is tightening rules. Australia is trialling an “age assurance” framework. More than a dozen US states, from Utah to Louisiana, have introduced or passed laws requiring users to verify their age before accessing social media or adult sites. You can almost feel the global policy mood shifting: after two decades of anything goes, governments are trying to retrofit an age gate onto the open web.

At first glance, the case for age verification feels like common sense. The internet has never been a particularly friendly place for kids. And so it seems sort of obvious that it would be healthier to put some checks in place.

Supporters argue that explicit or violent content, predatory behaviour, and addictive design all pose genuine harms — and that requiring age verification simply extends offline norms into an online space. You need an ID to buy alcohol, or to get into a movie with an R rating; so why not apply the same logic to pornography or gambling websites? Or now, as these proposals spread, to implement banning social media for the under-16s.

There’s also a moral appeal in appearing to hold tech companies accountable for the environments they create. For years, parents have been told it’s their job to supervise children online, but the power imbalance is absurd: a single parent vs a billion-dollar algorithm. By mandating age checks, regulators say they hope to force platforms to design with minors in mind — to stop monetising children’s attention, and to take responsibility for how recommendation systems shape their behaviour (though if you believe that argument, I have a bridge to sell you).

And politically, it always plays well. “Protect the children” is the kind of slogan no elected official can afford to oppose. Polls show strong public support for some kind of online age-verification regime, even if the details are fuzzy. The optics are irresistible.

The problems start when you ask how any of this actually works. If you think about it for more than a minute you realise this isn’t a case of kids proving that they’re under 16 and subject to the ban, but the rest of us proving that we’re old enough to be free to do what we like online.

Most forms of verification require users to upload a government ID, credit card, or facial image. That means centralising vast quantities of highly sensitive data — a honeypot for hackers (this is already happening), and a surveillance dream for anyone with access to it. As the Electronic Frontier Foundation says, there is no method of age verification that isn’t dangerous: an identity-tracking system masquerading as child safety.

Privacy isn’t the only concern. Researchers have found that biometric “age estimation” systems (the ones that analyse your face to guess your age) are less accurate for women and people of colour. Many adults simply won’t have suitable ID — migrants, lower-income users, or older people who don’t drive.

There’s also the chilling effect. Imagine having to scan your passport to access a queer forum, or a domestic-violence support site, or even a sexual-health resource. A lot of people, regardless of age, would simply choose not to. The more we normalise identity gates, the more we chip away at one of the internet’s founding principles: that you can explore, read, and learn without constantly declaring who you are. When access becomes conditional on identification, the people most likely to self-censor are those already most vulnerable: sex workers, queer communities, activists, whistleblowers, survivors.

The chilling effect isn’t hypothetical. We’ve seen it before. In 2018, the US passed SESTA/FOSTA, a law intended to curb sex trafficking, which instead drove sex workers off mainstream platforms and into far more dangerous conditions. Since then, every wave of “child safety” or “anti-porn” legislation has followed a similar pattern: blunt rules that make platforms overcorrect, scrubbing sexual content wholesale to avoid legal risk. Tumblr’s infamous 2018 porn ban, OnlyFans’ short-lived attempt to remove explicit content (hilarious in retrospect), and even Instagram’s moderation of queer art all trace back to the same playbook — conflate sex work with harm, and regulate it out of visibility.

Age verification continues that pattern under a new banner. Sites like Pornhub have already blocked access for users in several US states rather than comply with new laws, cutting off income for independent creators who rely on those platforms. And because “adult content” is rarely defined narrowly, these systems almost always sweep up sexual expression more broadly — queer stories, sexual education, reproductive health information, art.

The result is an internet that’s paradoxically less safe. It punishes the people who already face stigma and surveillance, while doing little to address the conditions that make young people vulnerable in the first place.

And then there’s the practical reality: kids are extremely good at getting around rules. VPNs, proxies, fake IDs, older siblings — the toolkit of evasion is endless. Age verification may well inconvenience adults more than it protects minors.

In short: it’s not that protecting kids is wrong — it’s that the solutions on the table create a whole new set of harms.

Is there any way to do this that doesn’t suck? Privacy-preserving technologies like zero-knowledge proofs could, in theory, let users prove they’re over 18 without revealing who they are or what they’re trying to look at — though these are still largely experimental. Platforms could focus on age-appropriate design and genuine parental controls, instead of punitive verification. And governments could invest in the boring but vital stuff: digital literacy, critical-thinking education, support for parents and teachers.

But what’s really happening here isn’t just a policy shift; it’s a philosophical one. These laws force us to decide who gets to define safety, and what we’re willing to sacrifice to enforce it. That’s the new piece of the puzzle I’ve been thinking about this week as I watch OpenAI roll out erotica as its business plan while your average adult content creator can’t get a bank account.

When regulators talk about age assurance, they often describe it as neutral technology — just another safety layer. But every identity checkpoint added to the web edges us closer to a “real-name” internet, where privacy and pseudonymity become privileges instead of defaults. That has consequences for everyone from queer teens to political dissidents to ordinary people who just don’t want their browsing tied to their legal identity.

This isn’t hypothetical stuff. This week the US announced that it was stripping visas from foreign nationals who had made social media posts about Charlie Kirk’s death, including “a South African national whose commentary attracted just 2,344 views”. Suddenly the idea of having to post up your government ID to send some silly tweets takes a pretty dark turn. An Olympian has been suspended for his Onlyfans account. When your age-verification scan for watching his content leaks, how is your employer going to feel about it? What if you want to run for local office? What if you’re on a school board in a conservative district? Library ebook apps let you borrow banned books, but for how long? Do the age gates apply here?

The history of “obscenity” law is itself a story of moral panic and prejudice — one that’s been used again and again to suppress queer and trans expression. From laws of the 19th century, which banned the mailing of any “obscene” material (a category broad enough to include information about contraception and gender variance), to modern moderation policies that flag trans bodies or queer intimacy as “explicit,” obscenity frameworks have always reflected the biases of whoever’s in power. When governments or platforms decide what counts as “adult,” they rarely mean straight, white, or heteronormative depictions of desire. Age-verification regimes risk hard-coding those same biases into the architecture of the web, making marginalised people once again the test cases for what’s considered acceptable to see.

As anyone who’s ever been carded at a bar knows, showing your ID is rarely the point. The point is proving who’s in charge.

more good stuff

i enjoyed collaborating with the crew at Hopeful Monsters on their new report 1000 Tiny Pieces, about what culture is like now that its so fragmented. There’s tonnes to digest here on fashion, sport, gaming etc. Definitely worth a read.

a few weeks back when we were talking about reality tv, I mentioned that I preferred the UK version of The Traitors with it’s all-civilian cast. I’ve been forced to eat my words now that the UK Celebrity Traitors has started. Era-defining telly, and not just because bestie Alan is hilarious in it.

go, you traitorous bitch

as an genAI skeptic with an open mind, I loved this experiment How does a blind model see the Earth? - in which the test is how a genAI pictures the globe as either land or not-land:

In the earliest renditions of the world, you can see the world not as it is, but as it was to one person in particular. They’re each delightfully egocentric, with the cartographer’s home most often marking the Exact Center Of The Known World. But as you stray further from known routes, details fade, and precise contours give way to educated guesses at the boundaries of the creator's knowledge. It's really an intimate thing.

fascinated by this article about Andor fans mobilising to boycott Disney/ABC in the wake of Kimmel’s suspension.

finally, in my lego city

Forward this email to someone you know is over 16, but make them prove it.

You just read issue #42 of what you love matters. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.

Add a comment: