Last week I finished Annie Jacobsen’s Nuclear War: A Scenario. The book is a non-fiction account of the projected aftermath of a North Korean nuclear missile strike on the United States. Not gonna lie: it’s bleak.

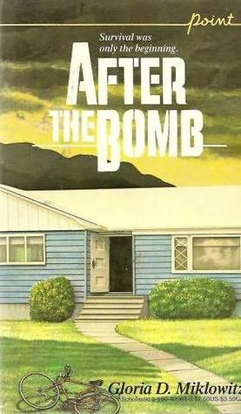

Books like this were my catnip as a child of the Cold War. I grew up reading On the Beach, and watching The Day After. I got this book from the Scholastic book club, age 10:

To this day I remember it because I had to look up what lactated ringers were, not really knowledge a child needs. In Britain, people were being permanently mentally scarred watching Threads. The Doomsday Clock was at three minutes to midnight.

In my early 20s, my favourite author was Douglas Coupland. He seemed preoccupied with the same terrors. In his book Generation X, there’s a chapter entitled “New Zealand gets nuked too”:

Otis had moved to Palm Springs because he had studied weather charts and he knew that it received a ridiculously small amount of rain. Thus he knew that if the city of Los Angeles over the mountain was ever beaned by a nuclear strike, wind currents would almost entirely prevent fallout from reaching his lungs. Palm Springs was his own personal New Zealand; a sanctuary. Like a surprisingly large number of people, Otis thought a lot about New Zealand and the Bomb.

But by then of course the Cold War was over, and we were living through a period of economic prosperity, and it seemed like nuclear armageddon was mostly in the rear view mirror. The Doomsday Clock was back at 17 minutes to midnight. Coupland wrote in Life after God about how we weren’t making disaster movies of the ‘70s like The Poseidon Adventure, Earthquake, Towering Inferno:

films nobody makes anymore because they are all projecting so vividly inside our heads—to be among the last people inhabiting worlds that have vanished, ignited, collapsed and been depopulated.

But then, some time in the early 2000s we started making them again. Digital and CGI made the dramatic depiction of the end of the world possible in a new variety of horrifying ways. Zombies rampaged through an abandoned London in 28 Days Later. Infertility brought the world to the brink in Children of Men. Inexplicably sideways-moving weather blanketed New York in The Day after Tomorrow. Viruses took us out in Outbreak and I am Legend and Contagion.

Young adult fiction embraced dystopia. As a genre, a YA novel needs an absence of adult figures for the heroes to have agency, so they need to be set away at boarding schools or summer camps, or in the bleak post-apocalyptic futures of The Hunger Games, The Maze Runner, or Divergent.

We traded the fear of mushroom clouds for asteroids, ebola, tsunamis, AI. Or maybe we just got tired. The Cold War ended and the movies moved on.

The thing about these new dystopias were that they are all fast ends. Everything changes in a a single televised speech. Civilisation collapses like a power cut. One minute you’re in a supermarket and the next you’re fending off zombies with a garden tool.

And there’s something addictive about that speed. No time to mourn, just run. It gives the illusion of control — that if you’re clever, or lucky, or good with maps, you might make it through. (I wouldn’t. I’d be eaten by a zombie immediately. I think it’s important to know your own limitations.)

Nuclear holocaust might be pretty fast for those at Ground Zero, obv, but for the rest of the world it’s an inching, reluctant inevitability. Something about that is fascinating to me in fiction. One of my favourite novels is Karen Thompson Walker’s The Age of Miracles — an elegiac coming of age story in which the earth starts to slow on its axis, making days and nights become increasingly longer. It’s a slowpocalypse; not an immediate race to the raping and the looting.

Now that we live in the constant shadow of all the various Horrors it seems sort of meaningless to fixate specifically on a nuclear end. The Doomsday Clock is at 89 seconds to midnight, but we have the climate crisis and genocides and authoritarian creep to deal with. And yet, in pop culture, our irradiated future seems to be becoming the new hotness again.

Silo, Fallout, and Paradise all explore the idea that (at least some of) humanity could shelter past the worst of it. The producers of smash hit Netflix show Adolescence is going to remake Threads into a drama show. Kathryn Bigelow is helming a new thriller about the White House scrambling to deal with an incoming missile attack. And Denis Villeneuve looks set to direct an adaptation of Annie Jacobsen’s book. What’s resurfacing is that particular Cold War flavour of dread: not the thrill of a speedy catastrophe, but the mundanity of surviving it. It’s not just death we’re afraid of, it’s enduring the aftermath. This is a beautiful essay about how On the Beach depicted this:

But it’s that small narrative pivot, from scenes of fiery ruin to an atmosphere of simmering expectation, that invests all these homely details with a creeping nightmarishness. Not that the temperature of the prose ever once rises; conspicuously, it does not. The characters each and all comport themselves with mildness and a distinctly Anglophilic style of polite restraint, like guests soldiering through a stilted garden party. All is strangely unemphatic. There is no high drama, no keening in the face of coming annihilation.

So it’s time to break out the radiation maps again. I guess the good news is that Coupland was wrong. According to Jacobsen, New Zealand doesn’t get nuked too:

We’ll just get the slow collapse afterwards. Like On the Beach, but with more Peter Thiel.

more good stuff

while we’re thinking about the end of the world, I was fascinated by this Canadian dev who has developed an operating system called Collapse OS designed to operate on scavenged hardware, using a programming language called Forth:

Forth communicates directly with the hardware. It controls a computer’s memory via commands called “Words” that you define on the fly. Because the foundational set of commands sitting under those Words is defined in native machine code, only a small part needs to be translated—meaning a smaller assembler and less RAM.

Benn Jordan saved a .png image to a bird. In case that sentence melted your brain, he converted the image to a spectrogram, played the resulting sound to a starling, and the bird repeated it.

Jameela Jamil is polarising, and unfortunately this is on substack, but it’s still Very Worth Reading (via SYSCA). The new It Girl is here:

Body Positivity was tricky for some, because while a brilliant movement in theory, it still kept us locked into thinking about our motherfucking bodies. “I love my thighs” is all well and good, but why are you thinking about your thighs at all, when there is this big brilliant world out there to experience and conquer? Orgasms to have? Memories to make? It was navel gazing, and sanctimonious and disingenuous to many women, and I think it pushed people away.

finally, in my lego city

Forward this email to someone who wasn’t depressed already.

You just read issue #31 of what you love matters. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.

Add a comment: