This week I’ve been thinking about helpers — the ones who keep our digital worlds running, immersive, and alive.

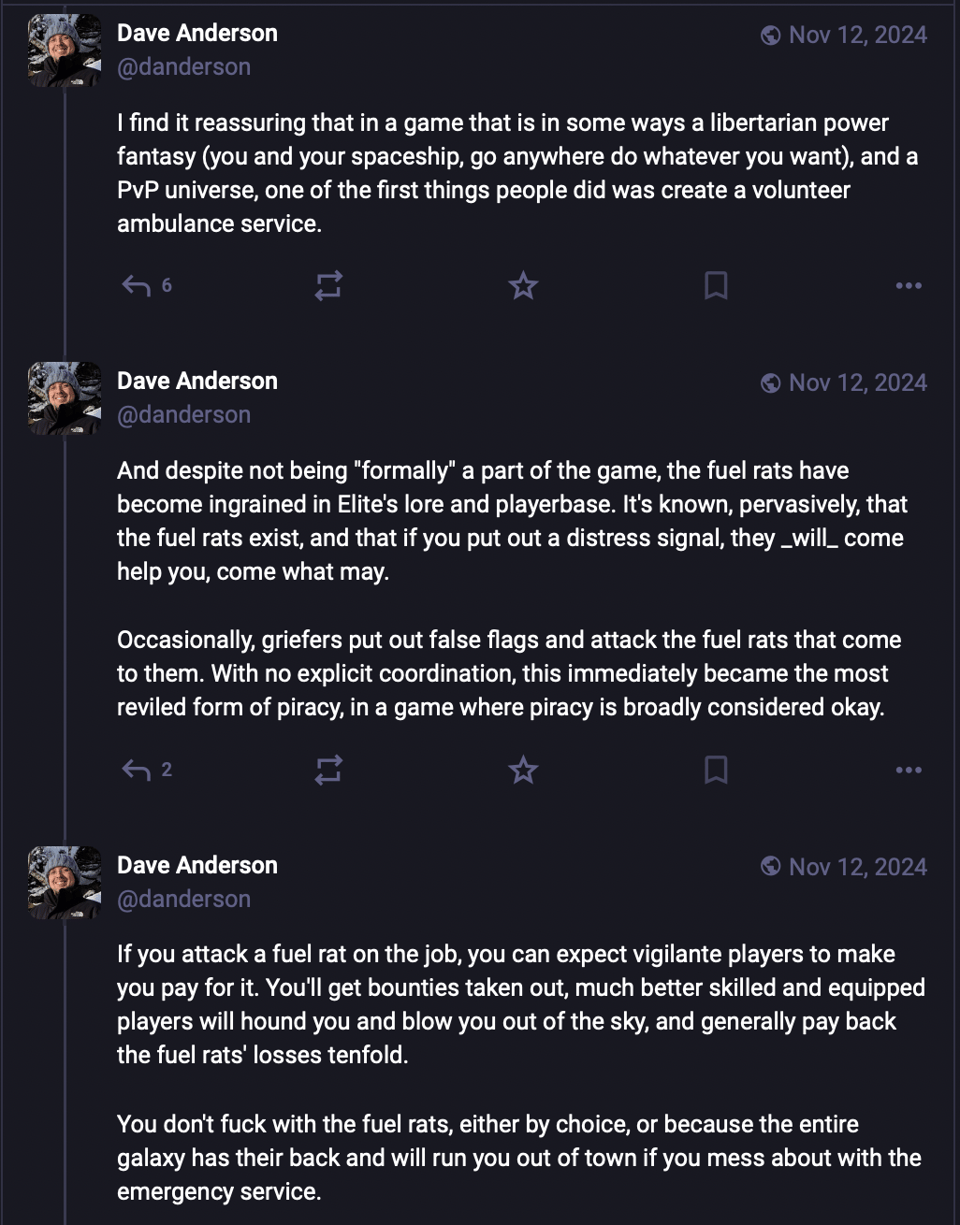

A while ago, Adam sent me a link to this thread about the MMORPG Elite Dangerous (Massively Multiplayer Online Role Playing Game — but in my head I just say it mmm-porg and move on). Elite Dangerous is a space exploration and combat game, where you command your ship around a 1:1 scale version of the Milky Way, and I don’t know if you know this, but space is massive. So in this game it’s entirely possible (particularly as a newbie) to plan poorly, run out of fuel, and then your ship is just marooned until you die.

But players in the game have, for years now, relied on the Fuel Rats — a player-run emergency rescue squad, founded on a whim and now over a hundred and sixty thousand missions deep. When you run out of fuel in deep space — far from any station, drifting helplessly through the void — you don’t rage-quit, you call the Rats. A dispatcher logs your location. A Rat (or two) jumps across the stars to refuel you. They take nothing in return, except the satisfaction of one more pilot saved.

There’s something mythic about it — like calling on a secret society that only reveals itself when you’re in real trouble. And yet it’s entirely mundane, too. Just volunteers, sitting at their PCs in bedrooms and kitchens around the world, coordinating in Discord and spreadsheets and IRC, keeping the universe stitched together.

I’m fascinated by communities like this — where helping is the game. Not glory. Not victory. But support, logistics, infrastructure. Roles that mirror real life, but are done freely, for joy and/or satisfaction. This Fuel Rat was asked whether there are any perks:

“No, nothing,” he tells me over Zoom. He has a swooping cowboy mustache and long hair pulled back in a ponytail, wearing a gray hoodie with series of patches and roundels on the sleeve, all awards he’s earned for rescues in the Rats.

“This pip means in my case that I have done over 100 rescues. This crest here means that you have done something especially outstanding for the Rats,” he says, pointing at a pair of golden laurels surrounding a very large drawing of a rat’s head. “They are not really relevant in-game, but you might display them in the forums or wherever. In-game there’s no benefit.”

I love everything about this. Similar groups will save your ass in EVE Online, and when the game was at its height, bring you medical supplies in DayZ (a zombie game):

One of my friends has recently got immersed in flight sims and I was staggered to learn that there’s a whole network of volunteer air traffic controllers — VATSIM, the Virtual Air Traffic Simulation Network. Thousands of volunteer controllers train, test, and staff virtual towers, ground frequencies, and en-route control centres. When you fly a virtual plane in Microsoft Flight Simulator, someone might be on the other end of the radio — vectoring you for an approach, issuing clearance, handing you off to the next sector — all with the same precision and language you'd hear from real-world ATC. Some volunteers even are real-world ATC. Others are just people like you and me who taught themselves how to run virtual airspace in their free time.

This is really rigorous stuff. Some VATSIM regions require months of training and multiple certifications just to control a small regional airport. It’s also joyful. There’s a kind of magic to the idea of logging in and finding yourself one tiny plane among hundreds, all coordinated in real-time by humans behind keyboards, pretending with care and accuracy to be the sky. Yes, there’s a LARP angle to this, but just also an enormous amount of altruistic labour.

And then there are the translators. The ones whose names you sometimes see tucked into the corner of a scanlated manga page or subtitled fan video. I’ve talked before about the fans who tirelessly translated the Norwegian teen drama Skam, episode by episode, scene by scene, subtitling and uploading in real time. The show aired online without subtitles, in fragments (social media updates, video clips, screenshots) and a decentralised army of fans built a kind of digital scaffolding around it so the rest of the world could follow along. They didn’t just translate the language — they explained context, memes, slang, and cultural references. They turned Skam into a global phenomenon because they believed in it. Because they wanted us to feel what they felt.

And then there are the tag wranglers: the unsung librarians of the fan archive.

On Archive of Our Own, tags are everything. They’re how we navigate millions of fanworks, how we search for a ship, a kink, or trope. But unlike hashtags on social media, AO3’s tags don’t just sprawl in chaos. Behind the scenes, a dedicated team of volunteers — the tag wranglers — link synonyms, standardise spellings, create hierarchies, and gently coax thousands of creative, chaotic user-generated tags into something navigable.

If someone tags a fic “Obi-Wan Kenobi Needs a Nap,” and someone else writes “Exhausted Obi-Wan,” a tag wrangler ensures they both appear under the broader umbrella of “Obi-Wan Kenobi.” If a ship tag is reversed or misspelled or phrased in seventeen different ways, wranglers sort it out. They work in multiple languages. They follow detailed internal policies. They maintain a living taxonomy that keeps the archive usable for everyone — without ever policing what fans can tag, just how it’s filed.

Linguist Gretchen McCullough, writing in Wired — Fans Are Better Than Tech at Organizing Information Online:

Laissez-faire and rigid tagging systems both fail because they assume too much—that users can create order from a completely open system, or that a predefined taxonomy can encompass every kind of tag a person might ever want. When these assumptions don't pan out, it always seems to be the user's fault. AO3's beliefs about human nature are more pragmatic, like an architect designing pathways where pedestrians have begun wearing down the grass, recognizing how variation and standardization can fit together. The wrangler system is one where ordinary user behavior can be successful, a system which accepts that users periodically need help from someone with a bird's-eye view of the larger picture.

It’s not glamorous work. It’s time-consuming, detail-oriented, and largely invisible. But it’s what makes the archive searchable and discovery possible. It’s fan labour at its most fundamental: entirely volunteer-run, quietly collaborative, and built to scale. Without tag wranglers, AO3 would be chaos. With them, it becomes a map.

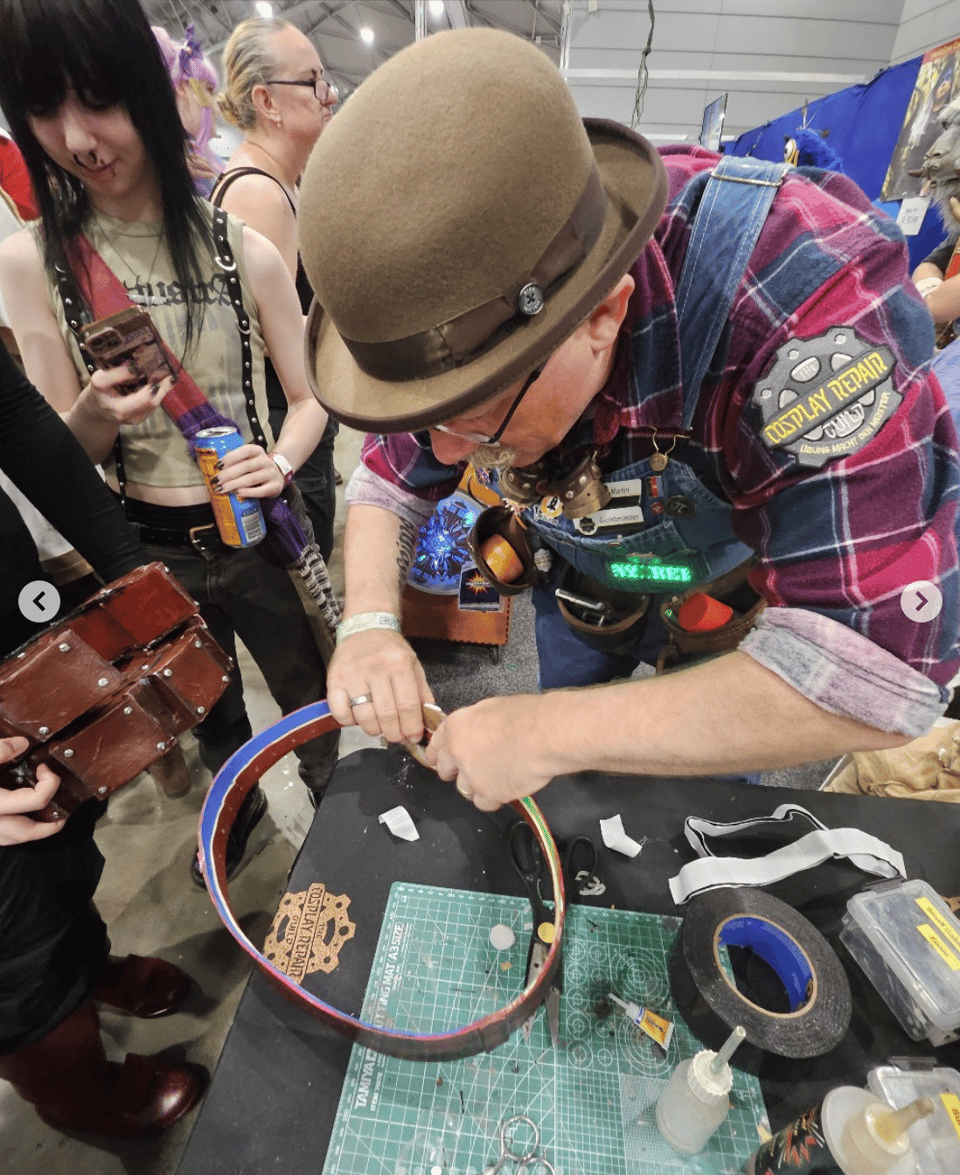

In the physical world, there's the Cosplay Repair Guild — a loose, affectionate network of makers and crafters who set up at conventions with glue guns, safety pins, hot irons, and sewing kits. They fix broken wings. Mend torn seams. Reattach armour. Calm nerves. They don’t ask what fandom you're in. They don’t charge. They just want you to feel like your costume is still worthy of the character you love.

It’s not just about hot glue and duct tape. It’s about care. It’s about recognising that sometimes we need someone to see us — to see our effort and say: you shouldn’t miss your moment because your EVA foam cracked. It’s about restoration — not just of the cosplay, but of your confidence.

All of these groups are part of a larger story I keep coming back to: the infrastructure of fandom. The systems and support that make things work, but don’t necessarily get celebrated. The unpaid labour that makes digital worlds feel real. This kind of help — meticulous, nerdy, generous — is part of what makes online culture so vibrant.

If you’re part of a volunteer crew — online or off — I’d love to hear about it. The ones you’ve built or lean on. Or the ones that once rescued you in a galaxy far, far away.

more good stuff

So much to chew on in this long read from Karl Ove Knausgård, The Reenchanted World, but I was struck by his visit with James Bridle, who says:

I’m not in the business of saving the world, but it would definitely be a better and more interesting place if more people were involved in making these things. That’s the fundamental thing: that if more software, more buildings, more social spaces, and more everything were designed by more people, of course it would produce a more interesting and better world! Such an obvious remedy. But there are reasons why that’s not how it is. One of Stafford Beer’s more famous and brilliant phrases was ‘POSIWID,’ which stands for ‘the purpose of the system is what it does.’ It’s a kind of maxim of cybernetics. And it’s very good for diagnosing systems. Instead of saying, Oh, we have a democratic system, we have an education system, you say, The purpose of the system is what it does. And what our society produces is people who are undereducated, or just educated enough to perform specific tasks—the way to get a good education is to study something that has this high economic value. Apart from that, you are pretty fucked. The purpose of the system is to reproduce the existing power dynamics of that system again and again. That is what it does. Society has no interest in educating you in how technology works. Because then you make your own technology, and you make different technology, and you upset the economic power balance and so forth. But it is doable, and people are doing it all the time. You can do it yourself.

wrapping paper that looks like bread!

i’m as tired of thinking about AI as you are, but I loved this from my friend Betsy, On stringing words together:

This is why using machines to make autocomplete-arrangements of words and tell ourselves this is speech, I think, is so egregious to me. When someone stands up to make a toast at a wedding, they are the one standing there glass in hand. What they are giving is their presence. The words that come out might be funny, or sad, or ironic, or really really awkward, and it’s finding out, right there right then, that makes it a toast. At a wedding. On a day. With people.

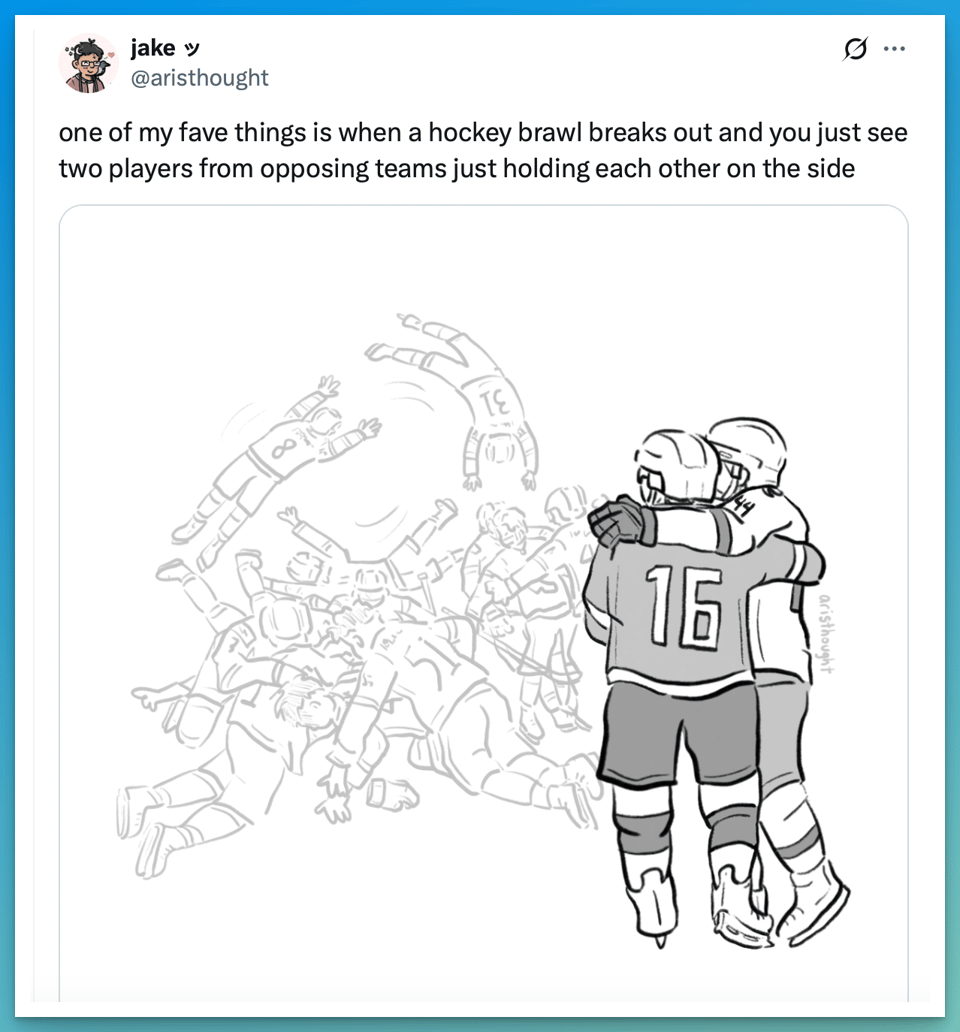

people always want to know why I became a hockey fan but literally it was this:

finally, in my lego city

Forward this newsletter to someone you think will like it. That’s your invisible fan labour for the day.

You just read issue #22 of what you love matters. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.

Add a comment: