Though it’s far from a new idea, there seems to be a fresh wave of articles going around at the moment about digital detoxing in its various forms. It might be the January of it all (new year, new you), but it predates that a bit. It’s the idea that we’re giving up streaming for vinyl or cassettes or mp3s, that we’re bricking our phones or switching to dumbphones or making our phones greyscale to reduce our dependence on them. It’s buying up old dvds or bluerays. It’s rawdogging flights (can imagine literally nothing worse).

And look, it’s a completely natural, healthy, human reaction when the world is as much of a dumpster fire as it is right now to want to tune out and do something (anything) else.

But I actually think that there’s a distinction here that’s worth exploring, that’s less between offline and online (or physical and digital) and more between queue and feed.

Feed is infinite and reactive: timeline apps, short-form video, autoplay video in your news media, “For You” pages, push alerts, what to watch next recs.

Feed is platform based. It sucks you in with dark patterns and it keeps you sat still and scrolling. It’s the everything apps, where you’re just as likely to see someone killed as you are to find you next fave song.

Queue, on the other hand, is bounded and intentional: an audiobook you chose, an album front-to-back, a downloaded podcast, a saved article, a library hold list. It’s things you’ve selected deliberately. That you already like, or that you’re keen to explore. It’s the tbr pile on your bedside table. It’s my Libby app pinging to say something I reserved six months ago and forgot about is ready for me.

Queue is long reads and four hour video essays. Queue is watching Heated Rivalry again and again and again because every other show I start has a women being murdered or stalked, losing a child or a parent or a job, or attracting the attention of a serial killer. Queue has a beginning, a middle and an end. It lets your brain finish a thought. It’s the difference between eating a meal and grazing from an open bag of chips — not morally, just neurologically. With queue you can actually arrive somewhere: a chapter ends, an album completes, a story resolves, your nervous system unclenches a notch.

But here’s the thing that I’m finding interesting. Feed is always digital, but queue is not always physical or offline. There’s a kind of snobbery (? is that the word I’m looking for) that comes from people who have eschewed their devices. Like vegans. They want to tell you how much more transcendent their lives have become and you feel weak-willed for still carting your phone to the bathroom.

But I think that attitude overlooks that it’s absolutely possible to use technology for queue experiences. Queue can be vinyl, sure — but it can also be Spotify in offline mode with your notifications off. It can be an audiobook on your phone while the rest of the phone is effectively dead to you (my fave is to put the audiobook on a portable speaker next to me while I’m lying outside in the sun). It can be downloading a podcast before you leave the house, putting the device on dnd or airplane mode, and letting yourself be a single-track person for forty minutes.

The point isn’t ideological purity or going full Little House on the Prairie. The point is choosing a thing, starting it, and not having it constantly interrupted by the platform yelling “and another thing!” at you. Digital isn’t the problem. The feed is. And a lot of the “detox” discourse misses that — it treats the phone like the villain, when the real villain is the business model that turns our longing for community into a firehose to the face of whatever keeps us looking.

And that’s the part that stops us detoxing completely: queue can be lonely. The thing that makes feed hard to quit isn’t lack of discipline — it’s that humans are not built to process the world alone. Sometimes you’re not looking for content; you’re looking for other people to look at it with you.

Queue is satisfying, but it’s solitary by design. Feed, on the other hand, is company. It’s not good company a lot of the time, but it’s company. It’s the winebar you wander into because you don’t want to be alone in your own head. It’s the background noise of other people reacting in real time, posting jokes, sharing outrage, doing little call-and-response rituals that make you feel like you’re not by yourself.

And that’s why the detox discourse always feels slightly wrong to me. Because what people are actually trying to quit isn’t “digital”. It’s the specific kind of digital that turns community into some kind of nightmare slot machine.

So yes — in an ideal world, we’d all be getting our “company” from real actual human people. From dropping by a friend’s place, or lingering after a thing, or becoming a regular somewhere, or building the kind of local life where you don’t need your phone to tell you other humans exist. And yes, as we spent all of last year talking about, we’d be better off if our online neighbourhoods were designed like physical neighbourhoods: smaller, slower, more legible, more accountable. Places you go on purpose, where you recognise people, where the incentive isn’t to keep you scrolling but to help you belong.

But we don’t live in that world yet. We live in one where community is fragmented, schedules are cooked, the news is relentless, and a lot of our social lives are genuinely mediated by screens. So “just throw your phone in the ocean” isn’t a plan, it’s an aesthetic.

My current rule of thumb is simple: if I’m reaching for my phone because I want nourishment, I choose queue; if I’m reaching for it because I want company, I try to choose a place (a group chat or my tumblr mutuals or a social slack). Feed is what happens when I don’t choose at all. If I don’t decide what gets my attention, the feed will, and it will always go for whatever keeps me looking regardless. Dedicating time and attention to things that I’ve selected, digital or otherwise, is the secret to taking that control back.

more good stuff

loved this essay from Katherine Dee about the latest rise in the manosphere and it’s historic antecedents:

The modern Manosphere inherits this aesthetic, adopting the symbols as though they were universal markers of arrival rather than compensatory performances forged under exclusion. What began as a response to being locked out of legitimate power gets recycled, abstracted, and repackaged, this time as timeless masculine truth. As so, to modern audiences, it reads as immature.

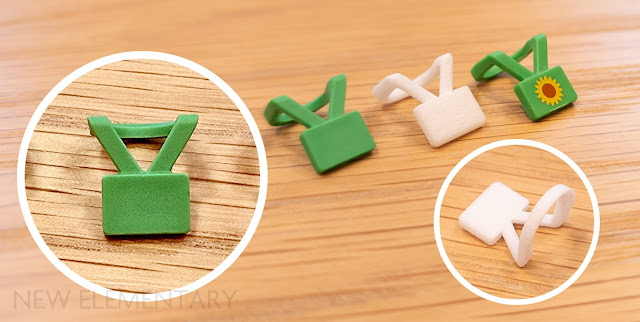

I just finished building the new 2026 modular Shopping Street, and so I was transfixed by this interview about all the new bricks/pieces coming out this year and the design thought behind them, including sunflower lanyards!

with the news that Dilbert creator Scott Adams passed away, I re-read this great essay about The Case for Shunning:

It’s such a weird thing to think about: the idea that we have destroyed Scott Adams’ reputation, simply by observing that he has said the things he said. That you should be able to hold onto your income stream after advocating a racially separatist state, as if being a racist fuckwit puts you in a protected class.

finally, in my lego city

Forward this email to someone who should throw their phone in the sea.

You just read issue #57 of what you love matters. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.

Add a comment: