This week I was on a bus behind a young couple and the guy was boring the girl to tears talking about the Very Exciting News that chatgpt-5 had been released.

Every time there’s a new model or hyped advance, I like to check back in on the LLM world and see if it’s hit the miraculous heights that zealots like to tell me will be arriving any day now. Surprise, surprise: even the zealots were largely disappointed.

Lately I’ve been thinking a lot about Gell-Mann amnesia. This is a term coined by author Michael Crichton to describe what happens when you read a newspaper (remember those?) and a journalist has written an article about your personal area of expertise. It’s full of errors, you roll your eyes and move on, but you trust the rest of what’s written in the paper as accurate.

That is the Gell-Mann Amnesia effect. I'd point out it does not operate in other arenas of life. In ordinary life, if somebody consistently exaggerates or lies to you, you soon discount everything they say. In court, there is the legal doctrine of falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus, which means untruthful in one part, untruthful in all. But when it comes to the media, we believe against evidence that it is probably worth our time to read other parts of the paper. When, in fact, it almost certainly isn't. The only possible explanation for our behavior is amnesia.

We’re now suffering a universal bout of something akin to this when it comes to generative AI. Ask most lawyers if they think LLMs are impressive and they’ll highlight the limitations, but those same lawyers will remark that it’s excellent for other things. Writers will quickly tell you how bland and tedious the prose chatgpt turns out is, but for non-writers it’s a great leap forward in crafting a difficult email, and the writers are happy to use it for — I don’t know — plumbing advice or scheduling their week. This Expertise Bias, a kind of artificial halo effect, seems to be convincing us all to buy into a kind of collective hallucination that genAI is significantly better overall than it is.

When you’re a bit of an genAI hater, as I am, people often joke that you’re just a Luddite. I’d always assumed I knew what Luddites were: people who hated new technology. But that’s not what they were about — it was an anti-capitalist, not an anti-technology movement. They were anti the version of technology that stripped power from workers and handed it to owners. It wasn’t the machines they were smashing; it was the economic system behind them. As Cory Doctorow writes:

The Luddites weren’t exercised about automation. They didn’t mind the proliferation of cheap textiles. History is mostly silent on whether they gave thought to the plight of tenant farmers at home or enslaved people abroad.

What were they fighting about? The social relations governing the use of the new machines. These new machines could have allowed the existing workforce to produce far more cloth, in far fewer hours, at a much lower price, while still paying these workers well (the lower per-unit cost of finished cloth would be offset by the higher sales volume, and that volume could be produced in fewer hours).

Instead, the owners of the factories – whose fortunes had been built on the labor of textile workers – chose to employ fewer workers, working the same long hours as before, at a lower rate than before, and pocketed the substantial savings.

The question, as ever, is who are these technological advances for?

If you want to read more about the Luddite analysis of the current moment, try Brian Merchant’s Blood in the Machine: The Origins of the Rebellion against Big Tech, or Jathan Sadowski’s The Mechanic and the Luddite: A ruthless Criticism of Technology and Capitalism.

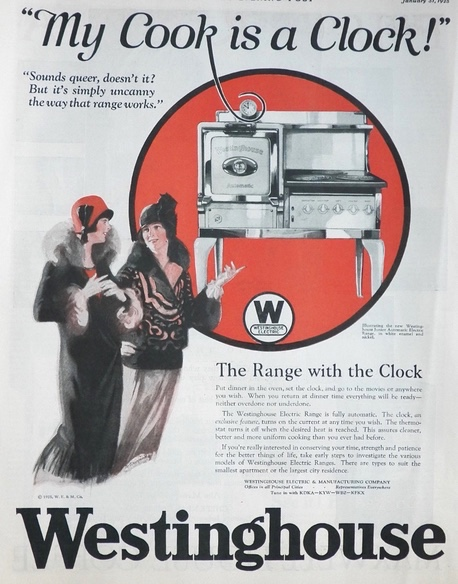

In the past, technological advances have almost always been sold to us with the dream of freeing us up to have more leisure time. You can go deep in a fascinating rabbithole about contemporary kitchen design, for example.

This episode of You’re Wrong About on the rise of the tradwife interviews Sarah Archer, author of The Midcentury Kitchen, and is great on this.

Of course, what actually happens when you put more appliances in a kitchen is not that women get to sit around in the garden drinking martinis.

One of the things that I think is lost a little in the genAI conversation at the moment is what we’re “freeing up” all this time for? When we’re getting the robots to write our emails for other robots to read, booking our vacations, planning our kids’ birthday parties, giving us answers to job interview questions asked by other robots — the idea is what, exactly? When we’ve efficiented away everything - what are we supposed to do with our days?

In the past, I’d have said it was the mythical idea of more leisure (while acknowledging the reality that we’ll be paid less for jobs that are more precarious, and so we’ll have to work even harder to stand still).

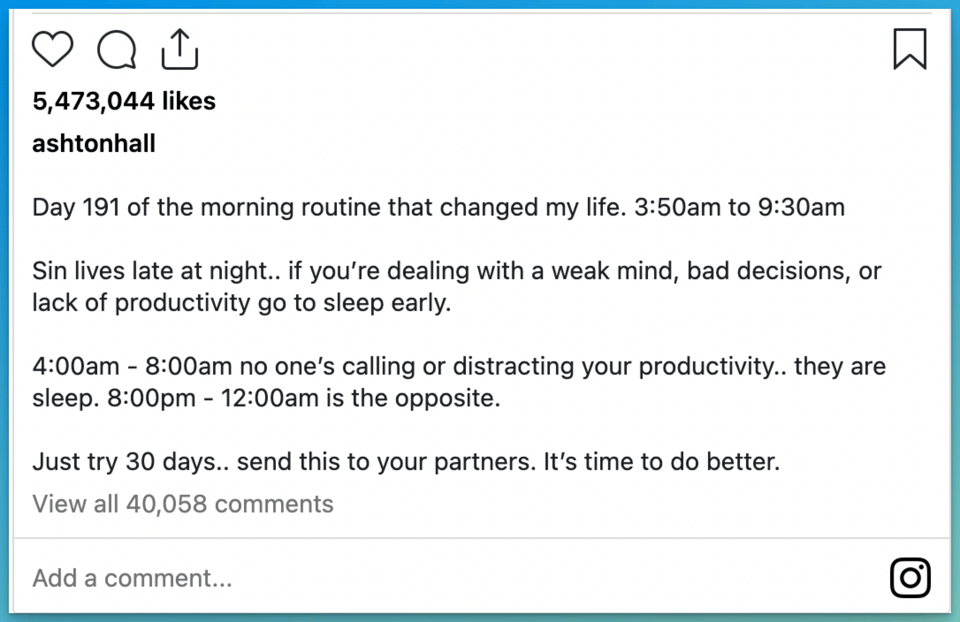

But what’s striking to me about the current moment is that the Silicon Valley grindhustle mindset doesn’t seem to be even hiding behind the leisure mask any more. The AI agents they’re promoting really are just designed to free you up to do more work. Influencers pedal morning routines that start at 4am with ice baths. LinkedIn posts tell you how to get agenticAI to do a day’s work for you while you sleep. If capitalism’s end goal is more capital then why would you stop? You never get to the martinis in the garden.

I’ve been in London this month during the Camden Fringe Festival, and I saw two shows that could only exist because talented humans wanted to make them. A couple of weeks ago I laughed myself stupid at Cayley Rae’s amazing Becoming Anne — a tight half hour monologue about what it’s like to look like Anne Hathaway. On Friday, I was lucky to see fellow kiwi Penny Ashton’s brilliant and clever Tempestuous — 90 mins of original Shakespearean comedy and songs in which she plays all eleven characters.

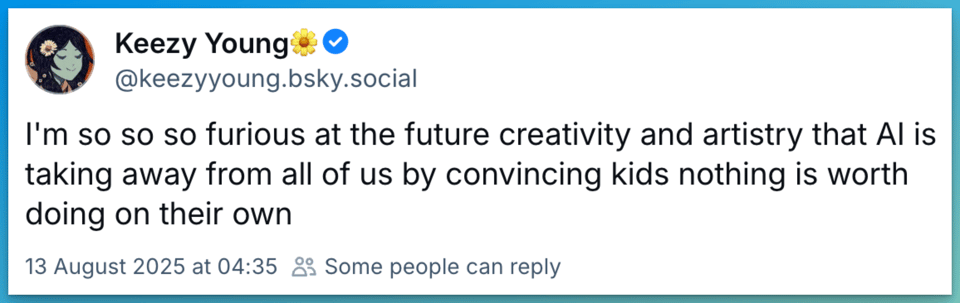

Meanwhile, genAI is dulling our brains, impairing our abilities to do the jobs we’re great at, and terrible at making art. As Ted Chiang puts it:

When you’re a student at a university, you should think of yourself as an athlete in training, and the job you'll do after you graduate is the sport you will compete in. You don’t know specifically which sport you will play, and neither do your professors. What your professors do know is that strength training will help you. That’s what essay writing is; it’s strength training for the brain. Using ChatGPT to write your essays is like bringing a forklift into the weight room; you are never going to improve your cognitive fitness that way.

Maybe that’s the real risk here. Not that AI will replace us, but that we’ll replace ourselves — swapping the messy, creative, fabulous parts of being human for optimised outputs and “efficiency gains” no one asked for except the broligarchs.

The Luddites weren’t fighting looms; they were fighting a future where skill, pride, and joy in the work were stripped away. And if we’re not careful, we’ll do the same because we forgot the point of making things ourselves.

If the choice is between a robot answering my email and a human making a play about looking like Anne Hathaway, I know which one makes life richer. And it’s not the one that promises I can get more done before the ice bath at 4am.

more good stuff

a few months ago we talked about Disney and Disney Adults, so you can bet I’ll be grabbing a copy of this book from AJ Wolfe:

Two decades later, Wolfe has forged a career out of her passion for Disney. Her popular Disney Food Blog reviews dishes served at Disney’s theme park restaurants, like a Mickey-shaped pistachio macaron at Epcot’s Sunshine Seasons, and a Lilo and Stitch-themed blue-and-purple milkshake from the Dockside Diner. And for her new book Disney Adults: Exploring (And Falling In Love With) A Magical Subculture (Gallery Books, Aug. 5) Wolfe mounts a robust defense of the people who, despite the stigma, have put the entertainment brand at the core of their identity.

voting is open for the Tiny Awards — you’ll recognise a few of the finalists from previous editions of these very bullet points. Get amongst and vote.

fascinated by this article about how current chart hits are “secular praise music”. Artists like Benson Boone, Teddy Swims and Alex Warren have tapped into a genre of music that sounds religious, but isn't:

“Musical tastes are cyclical, and this format is resonating right now because people are craving emotional release,” Roberts says. “We're living in a time where everything feels loud — digitally, socially, politically. These songs slow things down, pull you in gently and then give you that euphoric burst in the chorus. It’s a structure that mimics the arc of a personal breakthrough.”

finally, in my lego city

Forward this email to someone who knows how to spell blueberry.

You just read issue #33 of what you love matters. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.

Add a comment: