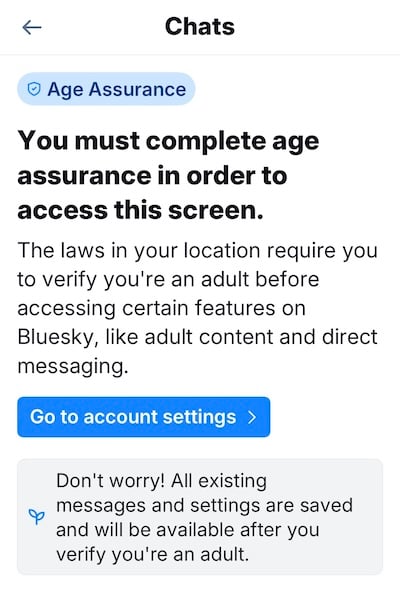

One of the things that hit me as soon as I landed in the UK last month was that I could no longer access my Bluesky DMs.

This is a result of Bluesky complying with the new Online Safety Act in the UK, which requires platforms that allow adult content to verify their users’ ages. Depending on who you talk to, this is a ground-breaking step to protect children from the harms of online pornography, or a privacy disaster waiting to happen. For example, in the US, anonymous messaging app Tea’s poor security measures meant 70,000 users’ government IDs and identification verification selfies were leaked online.

Of course, no age verification measures really work. UK users quickly discovered that you could use selfie mode in video game Death Stranding to pass the age checks.

Or simply use a vpn. Australia’s trial was similarly flawed. As the EFF notes:

the UK’s scramble to find an effective age verification method shows us that there isn't one, and it’s high time for politicians to take that seriously. The Online Safety Act is a threat to the privacy of users, restricts free expression by arbitrating speech online, exposes users to algorithmic discrimination through face checks, and leaves millions of people without a personal device or form of ID excluded from accessing the internet.

And, to top it all off, UK internet users are sending a very clear message that they do not want anything to do with this censorship regime. Just days after age checks came into effect, VPN apps became the most downloaded on Apple's App Store in the UK, and a petition calling for the repeal of the Online Safety Act recently hit more than 400,000 signatures.

The discourse around this is pretty predictable. The “all porn is bad, think of the children” crowd make age verification laws out to be a victory, when it’s really got very little to do with young people at all. Internet elders will remember the US enacting SESTA/FOSTA (and the ensuing porn ban on Tumblr, and the closure of Backpage) ostensibly to reduce human trafficking, which instead drove sex workers to the margins and far more unsafe conditions.

In the first in-depth legal analysis of SESTA/FOSTA and its impact, published in the Columbia Human Rights Law Review, Kendra Albert, Elizabeth Brundige, and Lorelei Lee concluded, in part, that “though the exact legal applicability of FOSTA is speculative, it has already had a wide-reaching practical impact; it is clear that even the threat of an expansive reading of these amendments has had a chilling effect on free speech, has created dangerous working conditions for sex-workers, and has made it more difficult for police to find trafficked individuals.” If SESTA/FOSTA was meant to associate sex workers with allegations of sex trafficking, leading platforms to refuse them service out of fear of increased legal risks, and in turn further marginalizing and stigmatizing sex workers, it was a tremendous success.

A good history of these campaigns, legislative reform, and the key involvement of payment processors in this hot mess, is here.

I’ve been thinking about all of this a lot this week as I spend time with my godtwins in Canada.

Thomas and Eleanor are eleven. They are, depending on your vantage point, either on the cusp of teenagerdom or still firmly children. Old enough to have been online for years already, young enough that they still have to ask permission before downloading a new app.

They both have smartphones, acknowledging that they’re young to have them and not all of their friends do. They go to school in Ontario, which has a phone ban in place during the school day.

When they have screen time at home (earned through chores), they both use it to watch Youtube or Netflix, preferring long-form content (animal videos, minecraft) to Shorts (Youtube’s equivalent to Tiktok or Insta Reels). Thomas says he hates the way time disappears watching Shorts: “You don’t even care what you’re looking at any more. You use up all your time and you’ve watched a hundred videos and you think ‘wait, what did I watch again? How did that happen?”. (you and me both, Thomas).

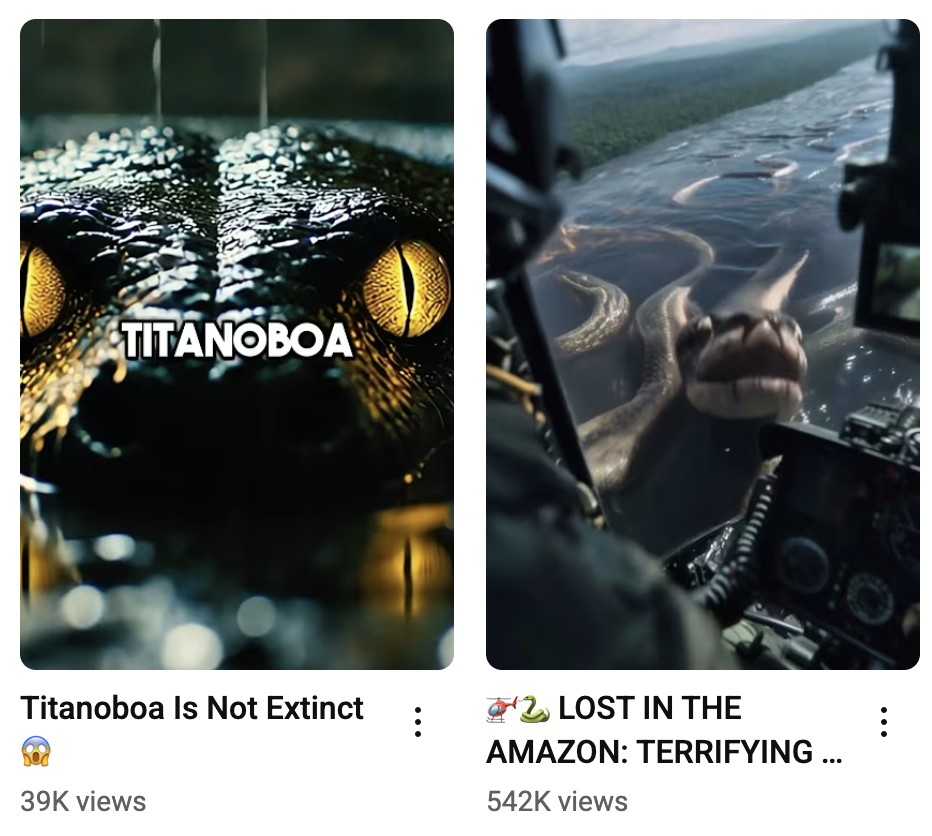

They’ve both noticed how much AI slop is creeping in to the videos they’re served. Eleanor says a giveaway is when the topic sounds strange or unrealistic. Thomas says AI videos have a “weird glossy look” and obviously fake titles.

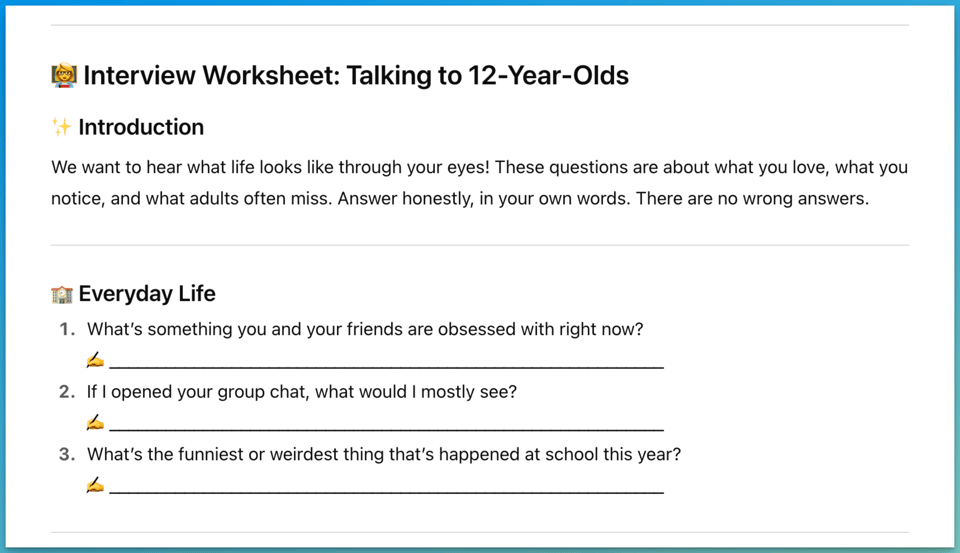

They know that Google doesn’t always give the right answers, and that they might have to dig around a bit to find what they need (“It tells you that if you cut a worm in half, you’ll get two worms,” Thomas says with disgust. “That’s obviously not true.”). Eleanor uses ChatGPT when she’s bored, getting it to write her stories about a cat or her dreadful older brother. Thomas says you can tell when a teacher has used ChatGPT to make a worksheet because of the “formatting, weird lines, and the emojis”.

They’ve done a “fake media” unit at school, where they learned that sites with obvious typos are probably fake, and videos about things they instinctively know aren’t real (like a Tree Octopus) should be viewed with skepticism.

Overall, Thomas and Eleanor seem to have a pretty healthy relationship with technology — but of course they’re young enough that they’re yet to be bombarded with the full teen diet of social media that those of us who grew up before the glare of everyone-posting-everything-all-the-time instinctively feel has to be the cause of a mental health crisis in the young.

But in truth, it’s a lot more complicated than you might think. This great review of Jonathan Haidt’s book The Anxious Generation captures it well, concluding “the evidence is equivocal on whether screen time is to blame for rising levels of teen depression and anxiety — and rising hysteria could distract us from tackling the real causes.”

These are not just our data or my opinion. Several meta-analyses and systematic reviews converge on the same message. An analysis done in 72 countries shows no consistent or measurable associations between well-being and the roll-out of social media globally. Moreover, findings from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development study, the largest long-term study of adolescent brain development in the United States, has found no evidence of drastic changes associated with digital-technology use. Haidt, a social psychologist at New York University, is a gifted storyteller, but his tale is currently one searching for evidence.

I firmly believe that bans are the wrong strategy. In the UK, a University of Birmingham study found students’ sleep, exercise, academic record, and exercise did not differ between schools with and without phone bans in place. The way we bring up a generation of young people who have a healthy response to being online is to teach digital literacy (in all its forms). In Germany, there's a volunteer organisation of 400 journalists called 'Lie Detectors'. Between them, they organise 1,000 school visits a year, training 10-15 yr olds how to spot fake news & pictures, the motives behind them, & the need for critical thinking. Finland’s coordinated approach to digital literacy has it topping the rankings for resilience to misinformation every year.

But the other kind of content the UK’s Online Safety Act is designed to deal with is content that encourages suicide, self-harm and eating disorders. And that’s also been top of mind for me this week, following the news of the first wrongful death suit to be brought against OpenAI (cw:suicide) after a teen took his life having confided in, and been encouraged by, conversations with ChatGPT. No amount of age verification, digital resilience, screentime restrictions, or touching grass is going to help when we’re allowing what amounts to a mass psychological experiment by a private company on the general public without any regulation, safety guidelines, or guardrails.

As I said two weeks ago, I get called an AI hater by friends and nemeses alike at the moment, but when your product stops talking to kids about cats and starts talking about nooses, we all have a role to play in smashing the looms.

Young people aren’t naive about the internet; they’re observant. They spot the gloss of AI slop. They roll their eyes at bad worksheets. They’re already learning to ask, “is this true?” Our job isn’t to lock the doors; it’s to hand them better maps.

Let’s teach them how feeds work, demand products that don’t prey on their attention, and back the people in classrooms doing the slow, unglamorous work of digital literacy. And when a product starts nudging a lonely teenager toward the worst possible outcome, the answer isn’t another selfie checkpoint. It’s real accountability, transparency, and — when necessary — a hard stop.

If we can manage that, maybe the next time I land in London my DMs will still be there and the kids I love will be safer not because we hid the web from them, but because we made it worth knowing.

more good stuff

Fantastic first-person essay from contestant Ruby Tandoh (archive) about her time on The Great British Bake-Off.

If you followed the drama around this season of Love Island UK, you’ll love this interview with the top three, The Real ‘Love Island’ Prize is the Friends Made Along the Way.

iconic trio Even if you’re yet to get on board the Kpop Demon Hunters train, this is a great piece about what’s made it such a success.

finally, in my lego city

Forward this email to someone who can’t put their phone down.

You just read issue #35 of what you love matters. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.

Add a comment: