Last year when we were talking about context collapse and the fourth wall, I spent a bit of time explaining fanvids. Then later we talked about fan edits, where fans recut movies or shows themselves to reflect a different story they wanted to tell. This week I want to talk about their gen z offspring, confusingly also called fan edits.

Fan edits, the way tiktok and insta users are deploying the term, are like fanvids of old — compilations of clips to tell a story, about a show or a central character or pairing — set to music. Here’s one about The Summer I Turned Pretty:

You can see the fanvid lineage, but there’s also some crucial differences. Edits are made for the shortform video content era, usually clocking in at well under a minute (where vids usually use an entire song). They’re cut like punchy little trailers - for a show, or character, or vibe — where a vid is often telling a full story in a few minutes. For example, here’s a fanvid celebrating queer joy, which uses the full track of Pink Pony Club:

And there are visual differences too. Edits are often heavily filtered. And they often have the lyrics to the song layered over the top (something that feels a little anvilly to older viewers). Here’s one for We Were Liars:

And perhaps the more significant shift is that edits can be about real people too, drawing on the Asian media tradition of fancams — yet another label for short clips or gifs focussing on celebrities. Confusingly this label has multiple meanings as well, because it also applies to footage of live performances where the camera only focusses on one performer, like my BTS bias Jimin. Famously, kpop fans will often rally to defeat snitch sites by uploading thousands of fancams.

Fanvids were historically not about the celebrities themselves — coming at a time when RPF was not as accepted as it is now. But in the everything-on-main era, your edit can support your ship and your ship can be as “real” as you like.

This is a great interview piece with a bunch of fan editors, the “greatest artists of our generation”.

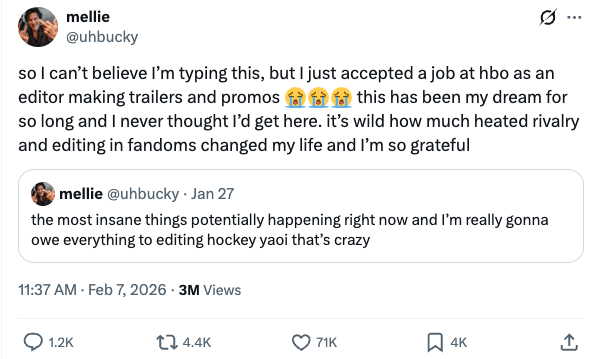

And as with all transformative work, what I’m most interested in is the value we attribute (or fail to attribute) to it. If you’ve ever tried to edit video yourself, even just to clip out your millennial pauses, you’ll know that it’s a real skill. Anytime I’ve cut a tiktok together, I’ve been left cursing the day I was born. And historically, as I’ve talked about at length, these skills developed by young women and non-binary folk are often not considered “resumé worthy” - because they’re in service of things we’ve historically denigrated (celebrities, pop stars, “guilty pleasure” tv). From What are fan edits, and why is gen z obsessed with them?

“What I’ve found in my many years of researching fans is that popular media tends to get concerned about fans being “too engaged” only when it’s a text that isn’t considered meaningful,” Booth says. “So, for instance, no one is talking about how sports fans create highlight reels. We don’t think they’re getting too engaged with real sports players. But when it’s a fiction show aimed mainly at a younger audience (and mainly female fans creating content online), we get into the realm of ‘negative’ experiences.”

But maybe that tide is finally, finally turning?

Late last year, Lionsgate started hiring fan editors to promote their movies:

Of course, any corporation attempting to engage in internet culture runs the risk of being the desperate “cool mom” who spoils the fun. So instead of trying to emulate viral fan editors, Lionsgate decided to hire them. Felipe Mendez, who manages the Lionsgate account, reached out to around 250 editors on TikTok and built a roster of about 15. “We’re going to the artists that fans are already obsessed with and saying: ‘We want you to create what you’re already doing; we just want to work together,’” says Mendez, who is 26.

And now, on the heels of Heated Rivalry’s astonishing success, HBO has hired someone who was making fan edits about the show:

You can see her phenomenal Heated Rivalry edit here. (Sorry it’s on the bad site — I have a whole other newsletter in me about why stans are still on twitter)

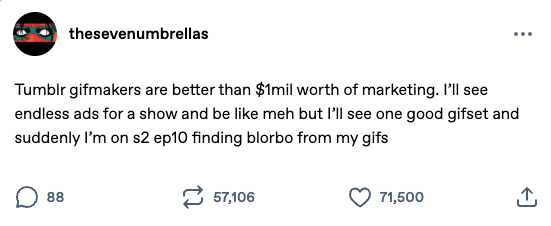

Obviously these are limited examples, but I think they point to something interesting. As transformative work comes out of fan spaces and floods mainstream platforms like tiktok and insta, it becomes impossible for studios and labels and rightsholders to overlook the impact that it’s having. How much more compelling the content created by audiences is than that put out through official channels, and how that directly translates into word-of-mouth buzz better than any paid advertising.

There’s always a tension when the industry pays attention: what happens to a practice once it’s folded into marketing budgets? Does it lose its edge or its joy or its community? But I can’t help feeling a little bit hopeful. Because what this signals — at least potentially — is a reframing. People who have always been labelled “obsessive teens with too much time on their hands” being recognised as skilled cultural creators. The concept of a piracy-adjacent nuisance of old seems to be finally being put to bed.

In an era where attention is scarce and authenticity is everything, the people who understand how to make you feel something about a story — quickly, viscerally, shareably — have real power. Fans aren’t just reacting to culture. They’re now shaping its circulation.

So keep an eye out for the next time you see a 38-second edit that makes you want to rewatch an entire series, or fall in love with a fictional hockey player, or care about a character you’ve never met. The work behind it isn’t frivolous. It’s taste-making. And increasingly, it’s a career path.

more good stuff

as discord rolls out age verification globally, it’s worth revisiting last year’s explainer on how flawed and political this all is. But also, a giant new study has shown that moderate social media use is better than abstinence for teens:

In the JAMA Pediatrics study, researchers at the University of South Australia looked at three years' worth of data involving 100,991 Australian teens and tweens. It included information on after-school social media use (defined as use between 3 and 6 p.m. on weekdays) and on various measures of well-being, including happiness, optimism, worry, emotional regulation, and cognitive engagement. The data revealed "a U-shaped association," where both social media abstinence and heavy social media use were linked to poorer well-being while moderate social media use was linked to better well-being.

this story is extremely me — anime horse cosplayers become Denver Broncos fans: A Horse Tries To Make It To The Super Bowl.

I liked reading this, from Korea, about the similarities between Bad Bunny’s iconic Superbowl halftime show and kpop:

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl LX halftime show carried an energy Korean audiences already recognize: the confidence of pop that does not need to translate itself to be understood. Before it became a spectacle of fireworks, choreography and the roar of the crowd, it was a statement about language as power — the idea that a global stage can be claimed without switching tongues, flattening accents or sanding away cultural specificity.

finally, in my lego city

Forward this email to someone who shares your blorbos.

You just read issue #61 of what you love matters. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.

Add a comment: