This week, along with 1.3m other people in the UK, I watched the finale of this season’s Love Island. If you’re about to close the email based on that alone, stick around.

When it comes to reality television, the shows I love best are ones where people get to demonstrate their expertise. I adore Project Runway and Bake Off. Keith Brymer Jones weeping over the beauty of the ceramics on The Great Pottery Throwdown. The incredible creations on Handmade: Britain’s Best Woodworker. I love these shows because I’m not really interested in drama for drama’s sake. The “I’m not here to make friends” vibe of most reality tv, particularly American, leaves me cold.

The other thing that ruins a compelling reality franchise is contestants who’ve watched multiple prior seasons and have come in with a playbook to win. The first season of The Traitors (UK) marked itself out with a cast of ordinary Brits who played the game straight because they’d never seen it before. The first season of the US version gave half the slots to former winners of other reality competitions — people who already knew how to scheme it up for the cameras. There’s a whole stretch of Survivor seasons that bore me senseless because it’s clear that the players determined to make it to the end have pre-planned every step in building their “resumé” for the eventual final vote. Look, it’s a game, I get it. It’s just not fun to watch.

Love Island, ostensibly, is about a group of hot singles in a Big-Brother-style living situation, trying to find love. Being accused of “playing a game” is one of the worst things that can happen to a contestant. You shouldn’t be trying to compete to win the £50,000. You can’t talk about the fact that you’re all there to bag the promo deals and sponcon once you leave.

And yet, now we’re twelve seasons deep that suspension of disbelief becomes harder and harder. Contestants move through a checklist of “exploring connections”, “closing off”, “going exclusive” and “becoming boyfriend and girlfriend” with the sort of perfunctory enthusiasm of being asked to hold hands in primary school. This season the fourth wall fractured further, with one “bombshell” (a late-arriving contestant destined to shake up existing relationships) torpedoed by a leaked voicenote she’d sent a friend outlining her strategy. Two ejected contestants returned with news of public sentiment from the outside. And one guy who clearly thought he was a frontrunner destroyed his own chances by repeatedly talking about the cameras and how he was being made to look bad on tv.

UK domestic violence charity Women’s Aid even released a statement on their instagram.

Reality TV isn't just entertainment, it shapes how people think about relationships, gender roles and what kind of behaviour is acceptable. When toxic behaviour goes unchecked on-screen, it sends a message that things like lying, gaslighting, emotional manipulation, and disrespect are just part of dating, or worse, that women should expect and accept this kind of treatment. When women's boundaries are ignored, when their emotions are mocked, and when bad behaviour is brushed off as "banter" or "just how boys are," it contributes to a culture where misogyny is normalised. This isn't just about one show, it reflects wider problems in society. What we tolerate on screen influences what we tolerate in real life.

Look obviously, all of this is A Show. The contestants are performing. We know they’re performing. They know we know they’re performing, and so on ad infinitum.

But it also reflects something more grim, as Teen Vogue (writing about the recent hack of the Tea app) puts it:

Straight-dating culture is in a tailspin because misogyny is being supercharged via digital-surveillance culture. The pressure to find a partner is compounded by the difficulty of attaining financial security. Hence, we have cash prizes on dating shows like Love Island and Love Is Blind, which titillate viewers while participants engage in increasingly intense games to skip the slow work of meeting people and finding someone who might fit your vision of “marriage material” or long-lasting partnership; who, as the saying goes, checks all your boxes.

Which makes Aisling Rawe’s The Compound such an interesting read.

In this dystopian novel, contestants start in an empty compound recently vacated by the participants from the last season, and have to compete in challenges and couple up to earn rewards and avoid being banished to whatever horrors lie outside.

‘I think that the way we’re living now,’ he said slowly, careful not to break the rules and mention that we were part of the show, ‘preys on the idea of desire. It amplifies it to the point of absurdity. You have to find someone to share a bed with, or you’re out. You have to make someone want to share a bed with you, or you’re out. And then they throw these tasks and rewards at you, and you keep living in this uncertain state, lurching between wanting and having. I think that must affect all of the decisions we make here, don’t you?’

And even though we know the contestants on these shows are real people, who will return to real lives outside the Villa, the manufactured nature of it all seems to give some fans the feeling that they can say or do whatever they like. That the contestants have declared open season on themselves simply by agreeing to take part. This year the producers of the US season of Love Island had to make a public statement after the online bullying, harassment and hate hit new heights. Contestants were ejected after racist comments they’d made in the past resurfaced. Stan wars erupted online.

Around the world, numerous Love Island franchises have demonstrated a worrying trend: when Islanders leave the villa and their 15 minutes of fame are over, they often face online hatred and vitriol for life. Vanna Einerson, who briefly appeared on the current season during Casa Amor, broke down in tears after she read comments from fans about her physical appearance. Amy Hart, a contestant on season 5 of Love Island in the U.K. testified in front of Parliament after she received death threats from viewers. Kendall Washington, a finalist on season 6 of Love Island USA, was subjected to homophobic remarks online, after explicit videos of him were released without his consent.

Maybe reality TV was never really about cake or handmade woodwork. Maybe it’s always been about performance — but the stakes of that performance have changed. These days, the shows aren’t just a mirror held up to our culture, they’re a two-way surveillance device. Everyone’s in on it: the producers gaming storylines, the contestants chasing brand deals, the audience playing judge and jury in real-time. What used to be a bit of escapist fluff now feels like a pressure cooker for late-stage capitalism, gender politics, and parasocial warfare.

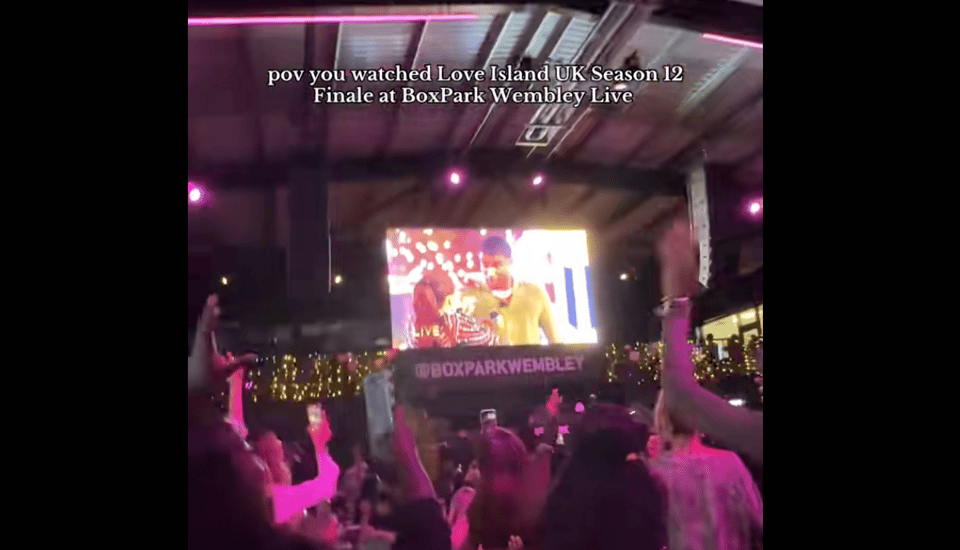

At this point we’re so far from the idea of finding love, it’s maybe better to think of the show as another live sport — the finale watched and cheered over in bars on giant screens.

Or stick to the purely fictional, rewatch UnREAL and marvel at Constance Zimmer and Shiri Appleby outmanoeuvering each other and reality tv in general.

more good stuff

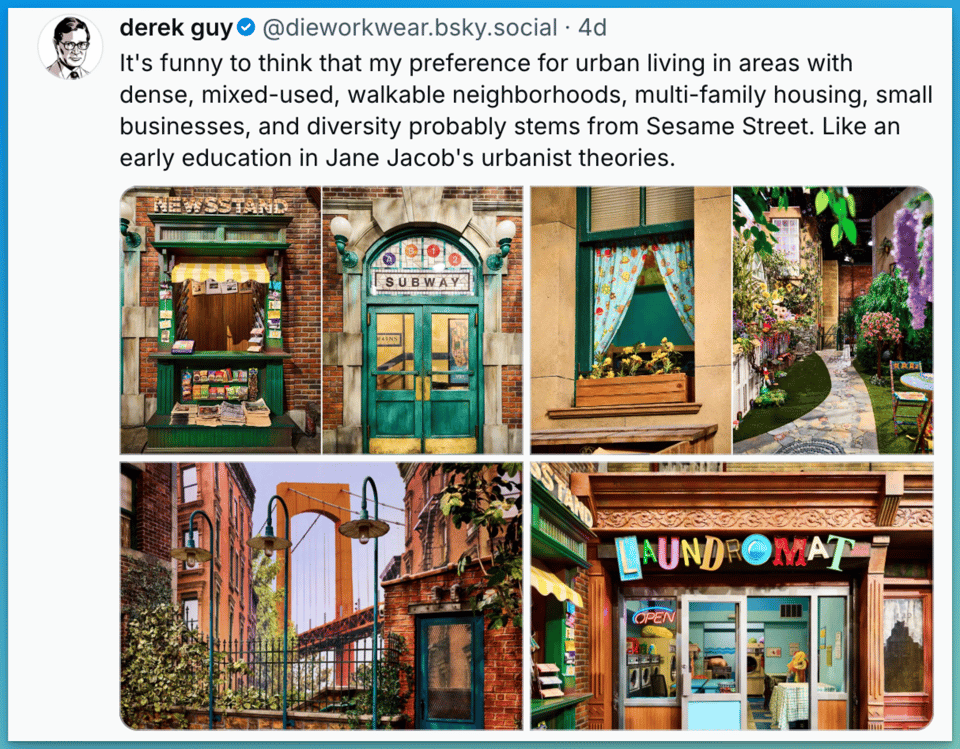

this is a great video from the NYTimes about the urban design philosophy behind Sesame Street.

i liked this, from History of the Web, We are still the Web: “The web is just people. Lots of people, connected across global networks. In 2005, it was the audience that made the web. In 2025, it will be the audience again.”

the news that Jim Acosta was going to “interview” an AI deepfake of a victim of the Parkland shooting this week (gross) is a great reason to revisit Anthony Oliveira’s A Trick of the Light: On the ethics of holograms.

What right, if any, does a person have to a 'Do Not Simulate' clause? To what extent, if any, can stipulation be made about what can and cannot be done with one’s image? What obligation, if any, do we have to the facts of history?

finally, in my lego city

Forward this email to someone you’re exploring your options with.

You just read issue #32 of what you love matters. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.

Add a comment: