One of my longest-running subscriptions probably is to Web Curios, a lovingly-tended weekly digest of weird, wonderful and deeply interesting links curated by Matt Muir. He also co-runs the Tiny Awards, which we’ve discussed a bunch here. I was lucky enough to meet up with Matt in person last year, and he agreed to chat before Christmas for this series.

Tell me how Web Curios started.

I was working at a now-defunct PR agency called Hill and Knowlton, part of WPP, back in 2010. We were forever telling clients it was incredibly important to “make content”, and so it was decided that we should also be making content, and I asked if I could write about things that might actually be useful to people working in marketing on the internet.

And bless them, no-one internally ever read it — which was brilliant. It meant I could write whatever I liked. There’s a famous early edition where I said all my colleagues were either on pills in a field at Glastonbury or snorting coke off the tanned midriffs of Central European hookers in Cannes. The head of digital in the US did not find that acceptable for a corporate blog. But yeah, I didn’t like my job and Web Curios gave me an outlet — and sixteen years later I’m still doing it.

What makes a good Curios link?

Something that makes you think, oh fuck. That oh fuck can mean a lot of things — “oh wow, that’s really interesting,” “oh Christ, that’s horrible,” “oh God, why are people doing that?” or “I didn’t know people were that into this weirdly specific thing.” It’s something unusual that makes you pause and go, that is curious, and I’m glad I know it even if I never want to see it again.

Is it about the internet, or about us?

The internet is us. We can blame lots of things for how awful it’s become, but ultimately we made it. It’s about people — strange, weird, obsessive, fleshy, occasionally mucal bits of people — expressing themselves through ones and zeros.

Has your taste changed over time?

Every nine months or so I’ll fall down a rabbit hole rereading old issues. It’s like time travel. Because it’s weekly, it accidentally tracks the concerns of the web — or society as expressed by the web. So it’s like a weird time capsule.

I wrote about NFTs a lot when they were frothy — not because I thought they were good, or they were going to become a life-changing thing for anyone, but because it was so curious that everybody had got suddenly so excited about the possibility. Then the last three years of AI-generated stuff.

COVID editions now read like a tiny time capsule. It's very funny looking back at that now, you get to you get to see all the different ways in which people attempted to either express their feelings about the pandemic or to build connections with the people using digital tools and that all of these things very very feel like much feel like moments in time. My interests haven’t changed that much; I’m a calcified middle-aged man. But the passions and obsessions of the world keep shifting, and Curios shifts with them.

Where do your links come from?

About twenty websites I cycle through daily, a hundred-odd newsletters, whatever floats across social media, and things people send me. A very wide net. I try to keep adding sources. One of the nice things about doing this is you get sense of…I was about to say tides, which sounds like a really unpleasantly pretentious metaphor, but fuck it, I'll go with that anyway… tides in the way that things change and the past three years have been a really interesting resurgence in people caring about this sort of thing in a manner that maybe in the late tens they didn’t. I find Substack problematic for a variety of different reasons: partly Nazis, partly because it's ecosystem capture (we’ve seen how that goes previously and doesn't end up with that for anyone). But one thing I will say about it though is that it's popularised the concept of newsletters and it's given a generic name to newsletters, for better or for worse. That means like every third person in the street will have heard of a Substack as a concept. And so the number of sources of my disposal has grown exponentially over the course of the past three years, which is good in a way, but also incredibly overwhelming.

Is it the rise again of old-school blogging?

Newsletters have basically replaced social media for me. Social’s dead — or at least no longer social. It’s just media now, tiny television. Twitter’s a nasty shithole; Bluesky’s a weird little enclave for people like us who remember the old days. Threads exists but doesn’t have any cultural impact.

No one sees their friends’ stuff anymore because algorithms killed that. Newslettering brings back the ability to find your people, the way early social once did.

So what’s your process?

I dump everything into a Google Doc during the week. On Friday morning I get up at six, read the overnight links, and just start typing. By noon I hit send. I don’t reread, I don’t correct — I write top to bottom until I run out of links and words.

If I wanted Web Curios to be popular, I’d make it better — shorter, edited, typo-free. But that’s not what it is. It’s me vomiting my brain onto the page.

I was going to ask you if Curios were a physical place, what would it be, but it sounds like you’re saying “vomit on the pavement”?

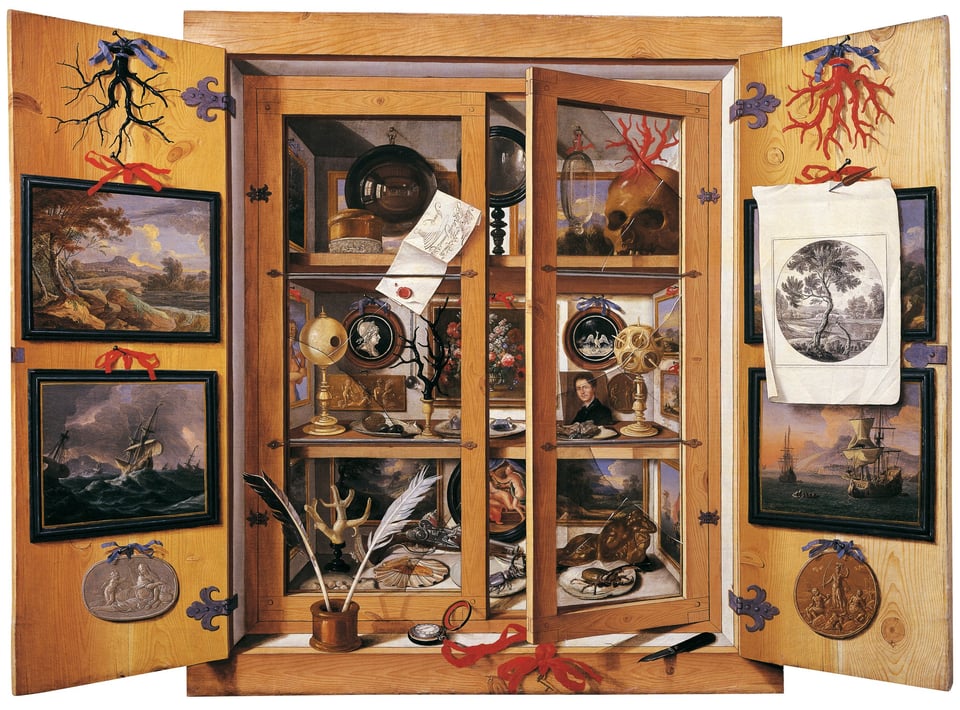

It’s the inside of my head. A fleshy case. Maybe an exploded cabinet of curiosities that smells faintly of gin.

What’s changed about finding things online for you in this post-search era? How do you think about discovery now?

One of the sad things is that social media used to be a regular source of interesting things. I spent a number of years on Twitter, not because I was a particularly good poster or because I was somebody who wanted to post but more because it was an incredible place for me to find interesting people sharing things. That doesn’t exist any more.

The dominance of data as the only determinant has flattened everything. Data steers you to the middle of the bell curve — which is rarely an interesting place to be. Very little good art comes from the middle of the bell curve, very little good literature or music or anything. Even interesting conversations tend to happen places that are just slightly off kilter to the very, very median. And unfortunately the data keeps on drawing us back to the median.

I think the other shift has been the the big move towards everything being image and video-led. Image and video are only one very small facet of creative expression and there's an awful lot more that people make with words and code and and all sorts of things and location, and those aren't necessarily always communicated best by by a full bleed 16:9 and I worry that that the other stuff is slightly dying. It does feel like that. Going back to the AI question, I think I am probably a lot more positive or a lot less anti-AI, than certainly lots of people who read Curios and maybe lots of people who will read this. But I do agree that that it is not going to have a good effect on firstly the quality of the corpus of stuff that is out there and secondly the ability of people to find good things in amongst the bad.

And so yeah, to go back to your original point, I think the curatorial stuff is more important, but it's also very hard to get to people. How many websites do you think most people visit on a daily basis?

I don’t know. A news website and something else?

Most people visit between six and ten sites a day — the same news outlets, the same shopping site, the same socials. Which, if you think about how much internet there is, it’s astonishing. To use a silly analogy we do this in real life as well. We shop at chain stores. We go to the same holiday destinations that TikTok has shown us. We love nothing more than seeing what five million other people have already done, and we do exactly the same thing and it kind of becomes a self-fulfilling semi-recursive idea. I find that somewhat dispiriting. I think if people who share stuff — weird silly interesting fun things — if they are doing one positive thing it is reminding people that there is a garden of the mind that exists outside of the algorithmic feed that you can access in just a few clicks.

Who reads Curios?

I have no analytics. No idea how many people subscribe or open it, and that’s exactly how I like it.

That's a really interesting decision. Is that because you feel like if you knew those numbers that you'd obsess over them? Or is it just genuinely not interesting to you? Or you don't think of it as a community that you want to shepherd?

Online communities are brilliant but managing them is hell. Moderating anything on the internet is one of the most horrible jobs in the world. I don’t want to do that. The idea of a Curios community feels hubristic.

Why don't I look at the numbers? Realistically because the information wouldn't make me happy. Honestly, whatever the number of readers is, it should be tons more.

What were your early internet influences — what shaped how you see being online?

I first used the internet in 1996 — half an hour per student on one computer, unsupervised. My mate and I immediately went to Bianca’s Smut Shack, obviously. Later at university I remember the sense of possibility. I discovered I could email musicians I loved — and they’d reply. Whatever I am interested in I can find someone else who might be too, and that was the most mind-blowing thing I think I've ever experienced and and I think that's characterised my personal web ever since. The idea that that it can connect people based on shared interests, and as we have now subsequently learned a lot of really bad things can happen, but at the time it felt utopian and wonderful and like no bad things could ever result from it.

Who are your curators — the people who will regularly send you down a rabbit hole?

I co-run the Tiny Awards with Kristoffer Tjalve, who writes a beautiful newsletter called Naive Weekly. He talks about “the poetic web” — small, personal, handmade sites.

I love Lynn Cherny’s Things I Think Are Awesome for tech and visual creativity, and of course Rob at B3ta, the grandfather of the UK internet. Rob’s work changed lives — he’s literally launched film directors’ careers. Doing Curios has changed mine too. It’s not made me rich, but it’s brought friends, collaborators, community. There’s something wonderful about helping odd little things find a life of their own.

Finally, what gives you hope for what’s next?

Everyone’s talking about how bad AI will be — and I get it — but I also think there’s something genuinely wonderful about the tools lowering the barrier to self-expression. We’re not far from a world where if you have an idea, you can make it real in a day.

Some of those ideas will be dreadful, but some will be brilliant. The important stuff will happen around the fringes, in the hinterlands — the weird little corners of the web. It's nice to know that there are still some people who are interested in different things and want to explore them and express them in different ways because not everything has to be on instatiktokgram.

——

Check out the previous conversations in this series with Cates Holderness and Sari Azout.

You just read issue #56 of what you love matters. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.

Add a comment: